There’s been a revival in the art of “packing” in recent years. Homesteaders Lianna Spooner and her partner Chris Eyer spend part of their year working with the U.S. Forest Service and nonprofits specializing in wilderness maintenance. This non-mechanized mode of transport helps preserve the land when carrying resources or personnel. We reached out to writer & photographer Sara Forrest to document a first-hand experience from the field.

Read the story below.

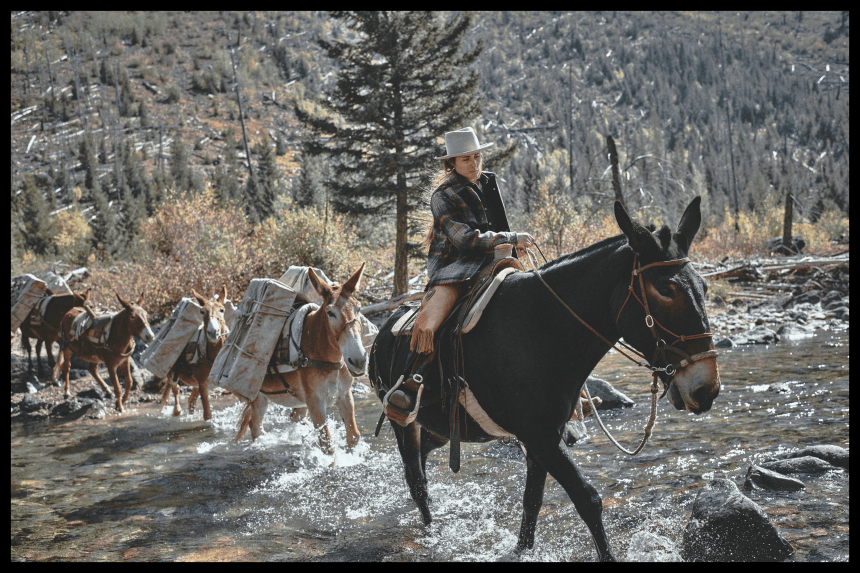

Lianna prepares to embark on a horse packing trip in the Bob Marshall Wilderness.SHOP NEW ARRIVALS

As I depart Montana, I notice my bag is coated with fine dust from sitting in the truck bed while traveling on the unpaved roads. There’s a familiar line of dirt under my nails. A normal occurrence, as my husband and I, have two horses and we don’t expect to stay clean for long during the daily routine. Yet this visit was hardly routine. When Filson contacted me about doing a piece on pack mules, I reached out to Lianna Spooner and her partner at the edge of the Bob Marshall Wilderness in Montana to learn more about the process. Not surprisingly, directions to their place in the valley included a left at a blue house, a right at a T junction, dirt roads, dust, passing a cluster of mailboxes, and finally crossing a cattle guard to get onto the ranch two miles down. Roads aren’t labeled much around here between the generational homesteads, many of which seem to be at least 160 acres. There’s no cell service or even much Wi-Fi to be found, which is a mixed blessing.

Packing a string out into this wilderness began in the 1930s and there has been a recent revival of interest in the art of packing as people strive for a deeper meaning, connection, and simpler life. Lianna and her partner Chris spend part of the year working with the U.S. Forest Service and nonprofits that specialize in wilderness maintenance and care. They use pack mules to transport resources like lumber, steel, hay, vegetation control supplies, and even other rangers into the wilderness. By protecting the deep wilderness clear from the encroaching onslaught of drive-by tourists, drones, electric machinery and tools, and other technology, this non-mechanized tradition of transport helps minimize the environmental impact.

To those who don’t know, a mule is a cross between a female horse and a donkey. Most of Lianna’s mules contain a mix of a larger draft horse mare and a Mammoth Jack donkey, resulting in big, strong, girthy animals. The bloodlines produce healthy, hearty equines with big eyes set further apart on their heads than horses. This helps them see more of their surroundings. Generally, these mules can withstand hotter temperatures than a horse, require less food while still maintaining their weight, do well traversing in snow, and have a calm demeanor. Horses are more likely to spook, spin, and bolt or flee if they see something move on the trail. These mules will generally freeze and wait for help. Lianna explained that a larger size breed works better in the rugged backcountry, where there are often large fallen trees and other debris on the trail. I was taken aback at the size of them and charmed by their playful personalities and eyes, which seem to peer straight into you. Each mule packs around 150 pounds. Often leaders ride horses at the head of the string because mules will always follow a horse, no matter where that horse falls in the herd’s pecking order.

“Packing is a job that you never really get used to, because every time you pack out there are different challenges.”

Sure enough, while we were out on the trail a rescue helicopter flew overhead. Lianna commented that in the wilderness you don’t get rescued unless something big happens, like breaking a femur. A broken ankle or busted knee won’t get you out. Even if you die, they won’t come and retrieve you. One time it snowed for 9 hours straight in the wilderness and all of Lianna’s warm gear and gloves got wet within a few hours. It being one of her first times helping on a pack trip, she quietly panicked and wondered how she was going to make the rest of the trip. She dismounted and walked to avoid hypothermia and ended up making it through a very challenging day.

In the horse world, you often hear trainers say, “Your horse doesn’t trust you.” I asked Lianna how she knows that their mules and horses trust in them—a question I am passionate about answering myself. I believe that mules and horses trust you when you’re consistent about what is OK and what is not OK, and you never put them in danger. You talk with your feet, you relax with your body, and you stay focused and aware and fair. You acknowledge that you’re aware of what they’re aware of and then create a working partnership based on being the leader and guiding them. If you don’t operate in this way, every time you get on their back your horse really won’t trust you. Lianna believes that it is also about a gradual and intuitive feeling that grows over time. She said that mules are often mischaracterized as being stubborn, but that is not true. Mules are preservationists. Often they just disagree because they feel their safety is at stake. They are highly intelligent and the bonds they create with their rider through thousands of miles together are strong and meaningful.

When not packing mules, Lianna is in the process of training an adopted mustang mare from Nevada that was known as a “three-strike.” Every time a mustang is offered up for adoption and does not get adopted, or is adopted and then returned, it gets a strike. After three strikes, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) can sell them to anyone, even people who will just take them to slaughter. Mustangs 10 years old and up can be sold “without condition,” meaning that anyone can buy them and do whatever they want, no matter how many strikes they have. But three strikes is the last stop for a mustang before it is sold “without condition.” Lianna estimates that this mare is between 8 and 10 years old. She was taken from the wild and then held for years on BLM land, spending some time at a training facility specializing in “green breaking” mustangs as much as possible so they potentially can be adopted out. The mare is a strikingly spirited animal—I could tell that the wild in her ran deep. Like the breathtaking landscape surrounding us, the mustang had a presence and wildness you could not mistake.

As I shake the Montana road dust from my pack, I find myself thinking back to this remote and wild place, and hoping to return next year. Of course, the wilderness is a place where you should always stay smart, plan ahead, be aware of things like weather and wildlife, and have some first aid and survival supplies on hand. A camper’s life was taken by a grizzly in July outside the post office in the town of 40 people where we stayed, and another grizzly was removed from the area a couple weeks back. Still, Lianna and I talked about planning a pack trip, and I’m already looking forward to heading back to Montana in the spring for another packing experience.