It’s a warm and muggy south Florida night as Donna Kalil’s 1998 Ford Expedition slowly rolls across the crushed rock and sandy surface of the roadway. Atop the vehicle, she and another volunteer silently squint into the thick grasses and scrub crowding the levee they are on. From her custom-made “Python Perch,” each look deeply into every nook and cranny as the bright LED lights mounted atop the vehicle briefly banish the darkness. Suddenly she sees something—a pattern that does not quite belong. Her heart starts to beat quickly and she calls out to the driver to “Stop!”.

“Yes, it just might be one,” she says quietly as she turns a spotlight toward the area, hoping to see the thick, muscled body of a Burmese python out on the hunt for prey. For another moment, with tensions high, she holds out hope that she has found a snake—but her light has revealed a large, twisted stick on the ground, not one of the estimated 100,000 to 300,000 Burmese pythons that are laying waste to the ecosystem of the Everglades area and surrounding regions. But that doesn’t deter her. It’s only midnight, and there are plenty more hours to hunt before the sun comes up and the snakes disappear back into the swamp waters to rest until the next nightfall.

Just about every night at sunset, Kalil heads out, often with a volunteer or two riding shotgun.

The snakes that she’s hunting are the result of a good idea gone horribly wrong. In the 1970s, the first Burmese pythons were imported from overseas as pets. They were a hit, and their numbers grew due to breeding programs and increased imports (importation has been banned since 2012). Released into the wild by their owners, they discovered an Eden in the Florida Everglades region, a place filled with food where they thrived. An apex predator, their only competition is large American crocodiles, alligators, and Florida panthers, and even those creatures can succumb to the pythons; nothing seems to stop them. The only other thing that can kill them in the wild is an extended hard freeze, which rarely happens this far south.

They quickly took to the waterways and started to feed, and feed, and feed.

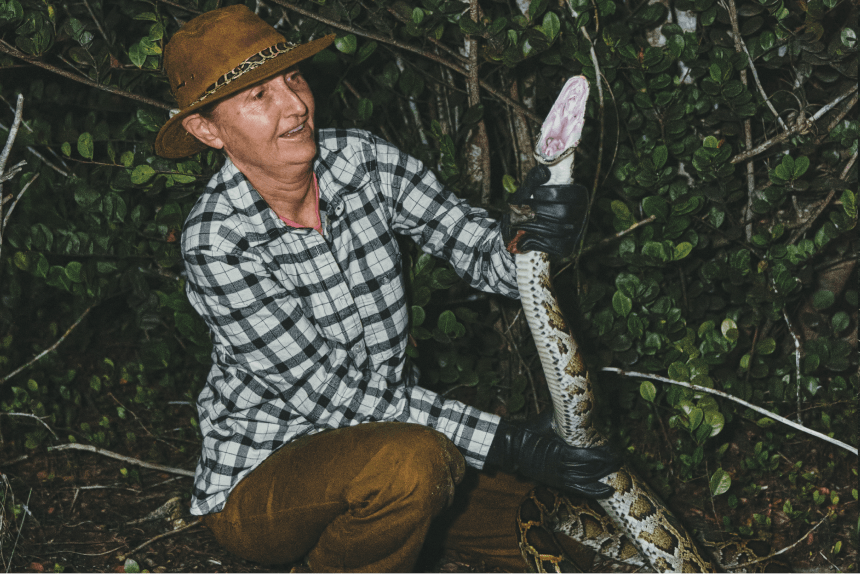

The night we joined Donna and her team we caught a 9ft Burmese python.Shop Tin Cloth

It is estimated that they have eaten almost every small animal in a delicate ecosystem that has existed in balance for over 5,000 years in just a few decades. “A substantial percentage of fur-bearing animals have disappeared from Everglades National Park and the surrounding natural areas,” says Mike Kirkland, an invasive animal biologist with the South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD). “Now they are starting to move onto the birds and other animals.”

Realizing that there was an issue, the state of Florida acted. Four years ago, the SFWMD and the Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission each hired its own group of contracted bounty hunters. They now number 100 in total. A motley group, they joined up out of their love for animals (many are snake lovers), and a deep concern for their native environment that many of them grew up exploring. They are paid minimum wage while on the hunt; $50 for the first four feet of a snake they capture, and $25 for each additional foot. A typical ten-footer, the size pythons grow to by the time they are three years old, nets them $200. They have brought in almost 7,000 so far in total.

Just about every night at sunset, Kalil heads out, often with a volunteer or two riding shotgun. Her Everglades Avenger Team is one of the most successful in the program. They have brought in over 500 snakes in the last four years. Growing up in the area, she fell in love with all snakes and kept several different types of native species as pets in her youth. Clad in long Tin Cloth pants, hiking boots, Filson’s flannel Alaskan Guide Shirt, and gloves, she’s ready to chase down her prey through the thick sawgrass and brush. Scouring an area that stretches from Florida’s southern tip north to Lake Okeechobee and the entire area west of Miami to the east side of Naples, she searches all night when the snakes come out.

When she sees one, she approaches it quietly from behind, moving ever so slowly, then lunges for its head with both hands. “Always go for the head. That way, they can’t swing around and bite you,” says Kalil. “They have over a hundred razor-sharp teeth that can tear skin up.” Using her body as leverage, she will force them down and quickly grab their tail. The pythons will use their tail to wrap up a snake hunters’ arms, legs, and even torso or neck if left unrestrained. Once it wraps around your forearms, it will squeeze, snapping bones in an attempt to escape. While they try to break free, they release a thick, smelly musk that makes them even more slippery. It’s dirty and exciting work. Once subdued, she puts the snake into a bag for transport to be humanely euthanized at the end of the hunt. out for humane disposal that evening. Catching one is like trying to wrestle a live fire hose into a suitcase. It requires focus and determination, and the bigger the snake, the fiercer the fight.

The program is part of a more extensive Florida Python Management Control Plan, which is attempting to better understand the problem and come up with solutions to remedy the mistake made several decades ago. While the people in charge of implementing this plan look at the data, contractors like Kalil are be out there every night hunting the mysterious giant pythons. “We put them there, someplace they should have never been, and we have to do something about it,” she says. “I love this area, and I want to help out. If that means I spend my nights hunting snakes, that’s fine by me.”