On July 18, 1882, a lieutenant in the US Army named Henry Hubbard Pierce (1834–1883) received a letter from Brigadier General Nelson A. Miles, who was commanding the Department of the Columbia, which included the Washington Territory. This communication outlined Special Order no. 97, which charged Lt. Pierce with carrying out an expedition of the North Cascades. The primary goal of the expedition was to map his route of exploration, starting from Fort Colville on the east side of the mountain range to his terminus in Puget Sound by way of Lake Chelan and the Skagit River. As the instructions outlined, his “reconnaissance is to obtain such knowledge of the country and its occupants as may be valuable at present or in the future to the military service.”

Pierce wasted no time in carrying out his assignment, officially under his command as the Adjutant of the 21st Infantry. This comes as no surprise, given his extensive military service record during the Civil War (he received numerous battlefield promotions, starting as a sergeant with the 1st Regiment, Connecticut Heavy Artillery, and finishing the war with the rank of major). He departed Vancouver Barracks en route to Spokane Falls as his departure point. Along with Pierce were a topographical assistant, Alfred Downing; an assistant surgeon, George F. Wilson; two enlisted men (musician Alford, and Sergeant Worrell). Another lieutenant, George Backus, Jr., joined the group on the way, having received orders to do so after completing another exploration assignment.

General Nelson Miles Commander Dept. of the Columbia

From Spokane Falls, Pierce set out with Backus and Downing to Fort Colville to secure pack animals along with provisions for the lengthy journey. They arrived without incident on July 27. Fourteen pack mules were used to carry the supplies, and two additional party members – a “competent packer” (unnamed) and a Native American guide named Joe La Fleur – had joined the group. The men also took with them 15 Cayuse horses and departed Fort Colville on August 1.

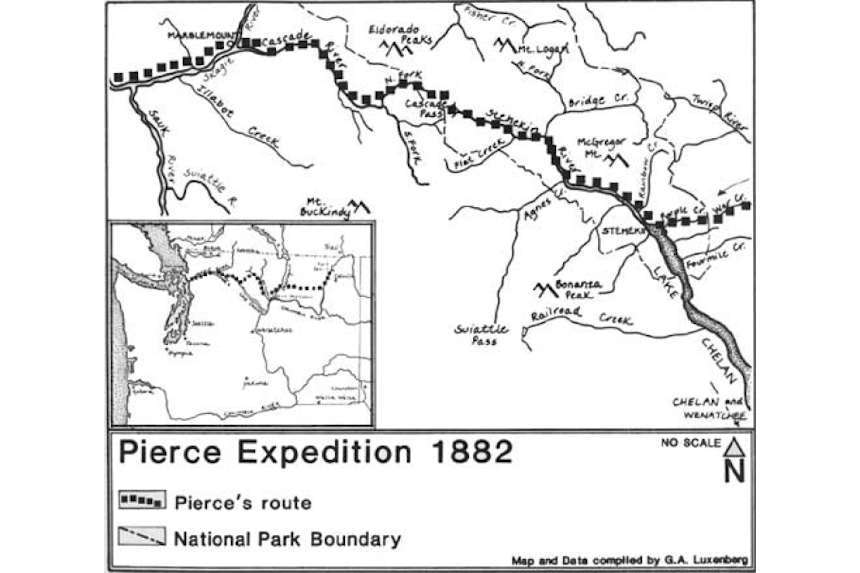

In his 27-page report based upon his personal journal, Pierce detailed the expedition’s passage that followed their departure from Fort Colville. Over 295 miles of terrain was covered by land and riverways, with the group crossing five mountain passes at an elevation of 4,000 feet, including Cascade Pass. Their journey followed the Stehekin River from the north end of Lake Chelan, continuing later to follow the Cascade River to the west, where it joined the Skagit River.

Pierce Expedition 1882 /National Park Service

Still true today, the terrain through the North Cascades is challenging, even for the fittest and best prepared parties. At several points, Pierce related how the effort took its toll:

“We began the wearisome descent of over three hours to Lake Chelan by a zigzag path along the back of a narrow, rugged spur [between Purple Creek and Hazard Creek]. After 9 miles, knee deep in dust, like ashes, filled with sharp fragments of rock, and constantly threatened by boulders tumbling from above, the almost perpendicular slope was accomplished. Reaching the canyon bottom, camp was made…on a sand-bar one mile from the mouth of the Pierce River [Stehekin River].”

Much of the journey by Pierce’s expedition was carried out on inland waterways. Starting from the Methow River, the group traversed the Twisp River to War Creek. Pierce also described how ferries were used for passage on the Columbia River. Their ascension of War Creek Pass was followed by Purple Pass, overlooking the head of Lake Chelan.

Pierce was a diligent reporter and captured many good details of his travels. Near the beginning of the expedition, where the group was transiting the Sin-pail-hu stream, he described the expedition’s “first delicious meal of mountain trout and tufted grouse, the former caught with a fly by Lieutenant Backus, an accomplished angler, and the latter killed by his unerring pistol.” Other descriptions offer an inspired vision of the landscapes through which Pierce found himself and boarded on rapture, as when the group reached the mouth of Celia Creek as they approached the mountain ranges of the North Cascades:

“While riding leisurely with my guide over a fine, grassy plateau, a glance to the left revealed through one of these openings a picture of such startling effect as to call forth an exclamation of surprise: two friendly peaks, apparently thirty miles away – the one shaped like the point of an eff, the other like a pyramid – lifted their snow-clad summits to the clouds. So grand and sudden was the vision, that I named them Wonder Mountains on the spot.”

“After 9 miles, knee deep in dust, like ashes, filled with sharp fragments of rock, and constantly threatened by boulders tumbling from above, the almost perpendicular slope was accomplished.”

Later, the expedition found itself less enamored with their surroundings, challenged to the point of quitting entirely. On August 26, Pierce and one other man (Alford) convinced the group to press westward rather than retreat to Colville; they continued over Cascade Pass. Pierce described the trail passage as one of the most difficult yet encountered, once the group reached the 5,050-foot summit:

“The pass is low and comparatively easy of approach from the east, but westward the descent is at first rapid and precarious. Packs were removed, and animals led down the steepest part.”

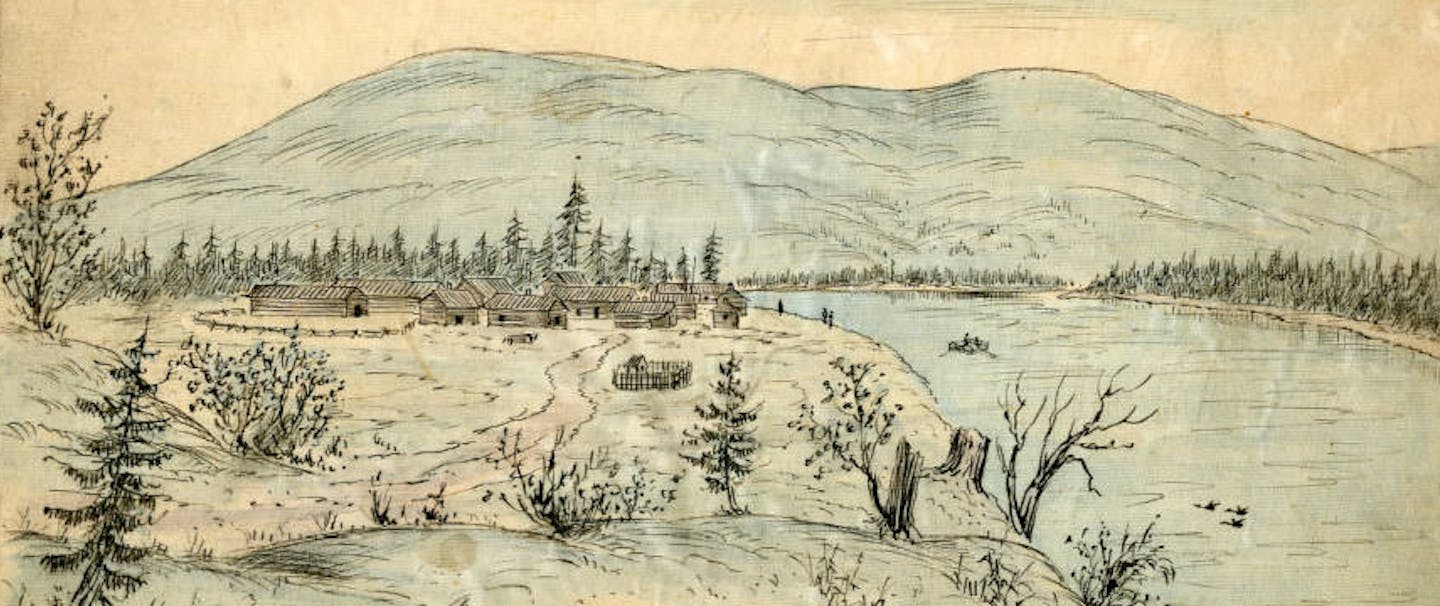

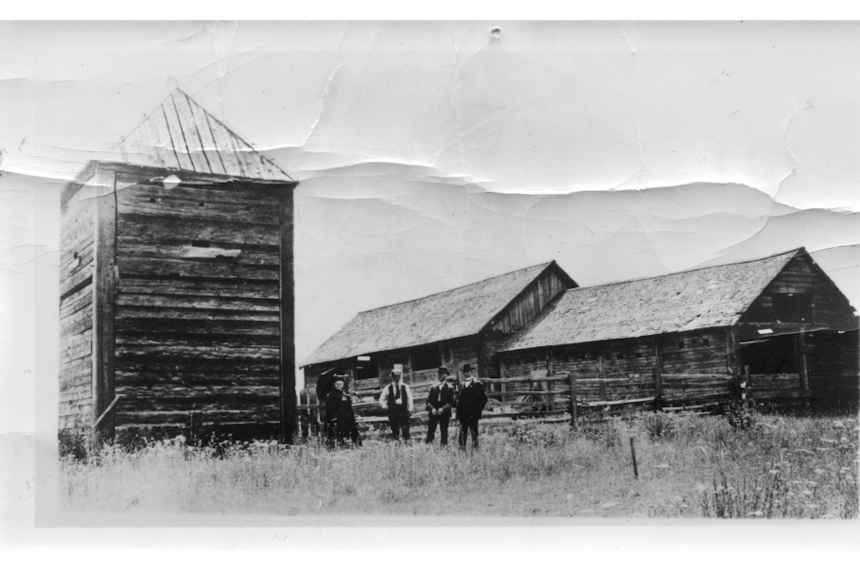

The final stretch on the Skagit River to the logging camp of Sterling was accomplished with the aid of purchased native canoes. Pierce remarked upon the final 70-mile leg of the expedition’s trek down the Skagit as “exciting by reason of the rapids, will be long and pleasantly remembered.” After a brief stay in Sterling, Pierce and the others took a steamboat to Mount Vernon on Tuesday, September 5, where the expedition members awaited the steamer Josephine, marking the conclusion of the expedition as a group. Today, the sketches of the expedition by Alfred Downing offer some fantastic views of the lands they passed through.

Pierce Expedition 1882 /National Park Service

In the months following Pierce’s official report to the U.S. Army, submitted on December 13, 1882, the Army stopped considering the North Cascades as a possible route for military purposes, since it was determined that the mountains were too impassable as a practical route.

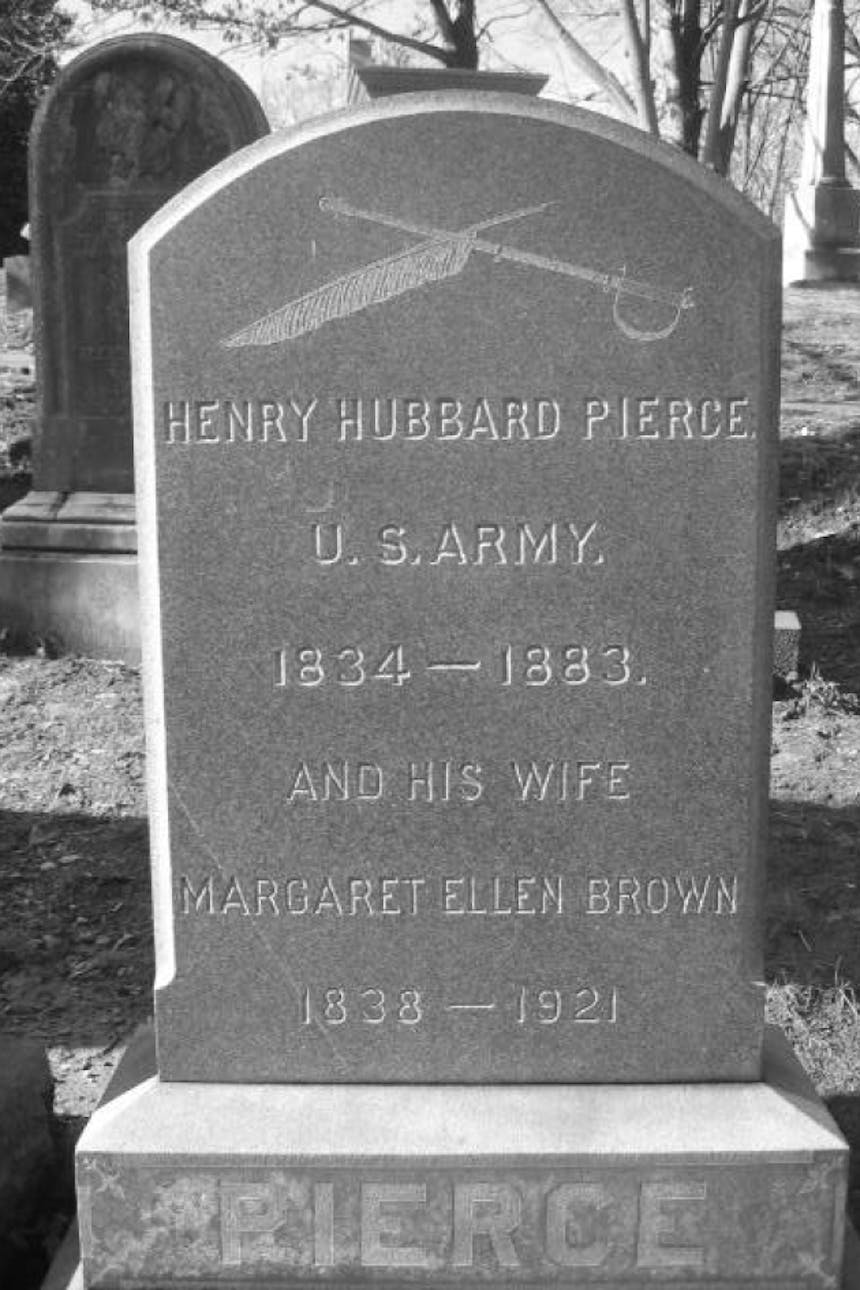

Pierce himself was destined for an untimely death. After he resigned as Adjutant for the 21st Infantry and accepted a position of military science at Pacific University, just six months following his report, he perished at Foster Creek, Washington Territory, on July 17, 1883, at the age of 43. He was buried in his home state of Connecticut alongside his wife, Margaret Ellen Brown. His commanding officer, General Miles, wrote a tribute to Pierce that appeared in the Oregonian newspaper, on July 27, 1883. Miles noted that besides Pierce’s ability to translate Latin at Trinity College and service as a lawyer, his Civil War record included the brevet of major conspicuous gallantry on the field of battle three times.

Henry Pierce gravesite in CT

On Pierce’s gravestone at the top are carved a crossed feather quill with a U.S. Army officer saber as a lasting visual testimony to a man who was both a soldier and a scholar in his time.

*Note: Several excerpts from Henry H. Pierce’s Report of an Expedition from Fort Colville to Puget Sound, Washington Territory (1883) are included here, with a copy of the report available today through the Washington State Archives in Olympia.