Nestled in the dense forests of Northeast Oregon stood Maxville, a former logging town that granted residence to African American loggers during the state’s exclusionary period, which saw Black people outlawed from the state. Despite the odds, this timber town thrived and prospered amidst adversity to become a boon for Black men and their families to flourish.

Friendships Say No to Jim Crow, c. 1937 - Despite Bowman-Hicks' enforcement of Jim Crow-inspired segregation mandates, Maxville's isolation from mainstream society encouraged the formation of interracial friendships. Black and white townspeople socialized and often shared resources. When Bowman-Hicks ended its logging operation in 1933, the Black and White schools desegregated and the remaining Maxville children attended school together, taught by Madeline Riggles. Both Black and White loggers from the South, local loggers and homesteaders logged Maxville. Photo provided by Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center

Extending from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific coast was Oregon Country, an expansive and disputed territory where settlers developed the Oregon Trail, a route that stretched over 2,000 miles from the Missouri River to valleys in Oregon. Incentivized by the Oregon Donation Land Claim Act, thousands of emigrants traveled toward the Western frontier in the hope of a new start. Surrounded by abundant bodies of water, serried evergreen forests, mountain ranges, and an extensive coastline, it was prime real estate. Yet, not all were willing to make this pristine terrain hospitable to everyone.

Post Office and Payroll Building, c.1925 - Photo provided by Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center

In 1844, the Provisional Government of Oregon enacted several laws that excluded Black people from owning land and residing in the territory. As the thirty-third state entered the Union in 1859 as the first Whites-only state, their stance was made clear, which discouraged many Black people from migrating there. Even so, many were not deterred by such menacing legislation.

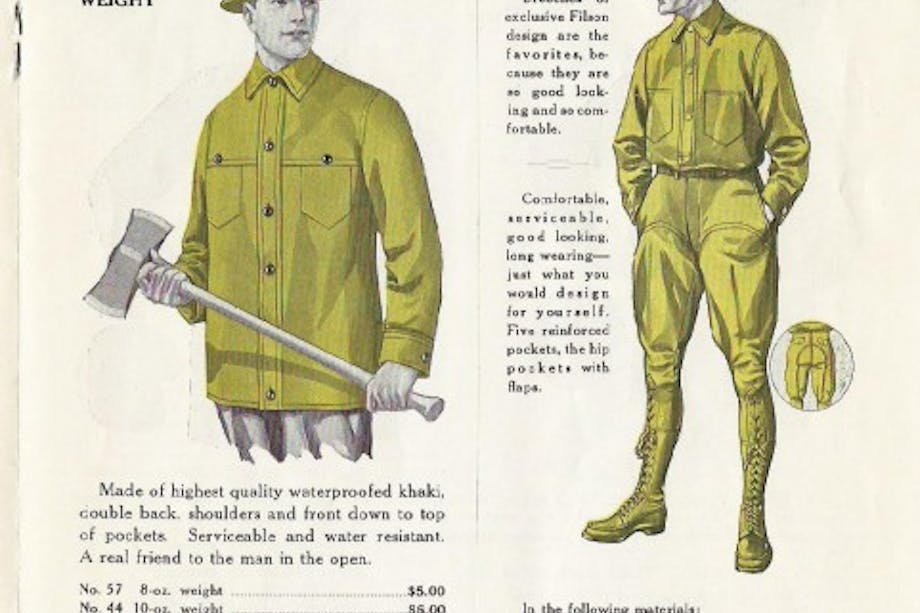

By the early 1900s, American loggers’ interest had shifted further west as timber supplies dwindled in the upper Midwest. Businesses like the Missouri-based Bowman-Hicks Lumber Company saw the opportunity and recruited hundreds of qualified loggers, forty to sixty of them Black. Indifferent to Oregon’s racial allegiance, the company moved its multiethnic employees into the newly founded town of Maxville. Toward 1923, it was the largest town in Wallowa County, as well as being the only town in the county to have Black citizens; despite just a year prior, Walter Pierce–a prominent member of the Klu Klux Klan–being elected governor of Oregon. Still, this was merely a drop in the bucket for Bowman-Hicks as they had more important tasks to tackle, which was harvesting timber to supply the masses.

Pseudotsuga menziesii is an evergreen conifer species in the pine family favored for logging. It is native to western North America and is commonly known as Douglas fir, Douglas-fir, Oregon pine, and Columbian pine.

Maxville Logger Company Photo, c.1926 - The loggers stand with tools they used daily. The men with long poles and axes measured the board feet to the standard length. The men with crosscut saws, known as sawyers, cut the trees and worked in pairs, usually with someone they knew. Matching your partner was critical to rhythm and speed, the more trees you toppled meant more revenue. Photo provided by Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center

For leisure, there was a natural swimming hole and two baseball teams. “They had an opportunity to work side by side, save each other’s lives … and when they celebrated, they celebrated things together,” said Gwen Trice, Executive Director of the Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center. When the teams integrated, they won a tournament in nearby Elgin in the mid-1930s. Unlike most logging camps during that time, Bowman-Hicks wanted to provide a good work-life balance for their workers toward a common goal, which in turn helped the residents to get along well with one another. Maxville thrived on lumber for many years until the Great Depression abruptly caused the lumber market to downturn—the catalyst to the town’s eventual decline. In 1933, Bowman-Hicks officially ceased production and closed the settlement down for good. Many African American families moved to local cities in Oregon, while some moved to Washington and California for new logging and shipyard work. Some loggers even stayed behind in Maxville up until the 1940s, eventually moving away after a blizzard destroyed what was left of the area.

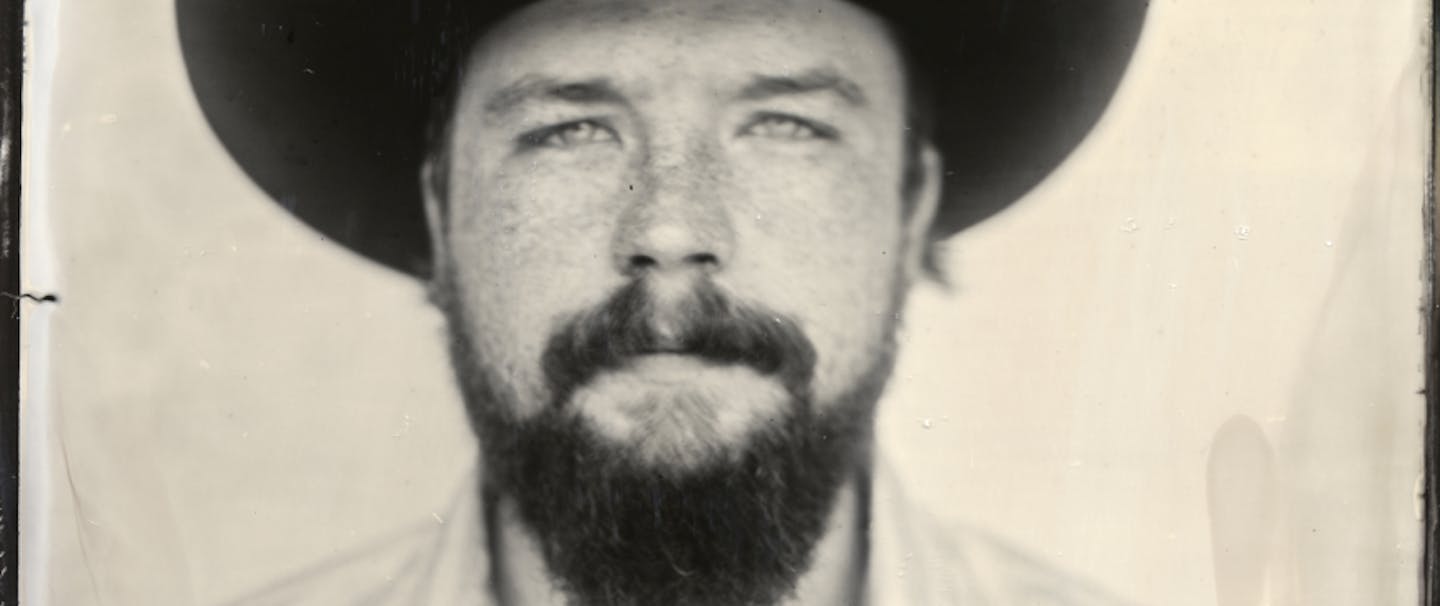

Today, Maxville’s memory is kept alive by a descendant of one of those spirited loggers, Gwen Trice, who has worked tirelessly to preserve its nearly forgotten story and to secure its place in Oregon history.

Gwendolyn Trice, Executive Director at Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center. Photo provided by Joe Whittle.

This article was written by Kayla Tunstall from @BlackHistory, in collaboration with Filson and the Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center.