During the eighteenth century, the drinking to excess of rum and other spirits was considered an everyday part of the life of many “pyrates” (Old English) who plagued the oceans of the world.

–

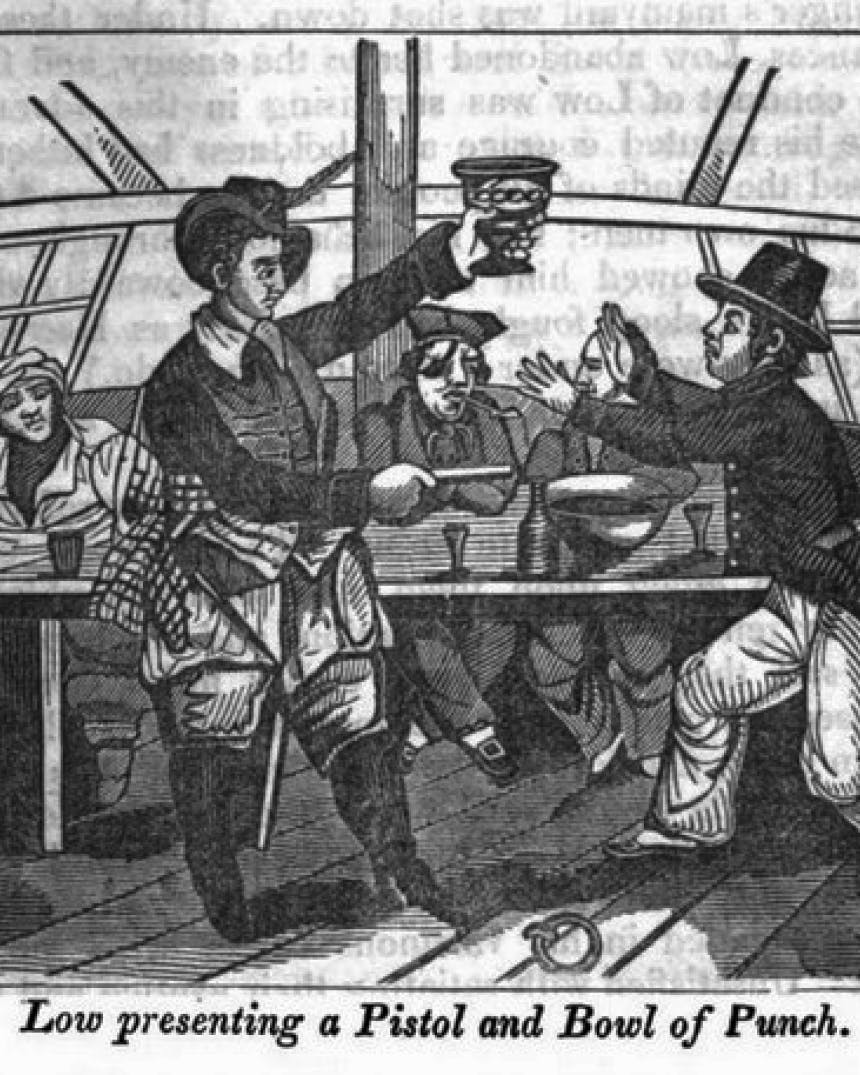

One Captain Edward Low, a pirate notorious for his cruelty and barbarism, once made a captured fellow captain drink up to a quart of “punch” liquor at gunpoint, telling his prisoner “he should take one or the other.” Like many pirates, Low came to a bad end. Along with 25 of his shipmates, he was found guilty of piracy and executed (read: hanged, or did “the Dance with Jack Ketch”) on July 19, 1723, near Newport, Rhode Island.

The spoils of captured merchantmen vessels often yielded large cargos of rum, wine, and ale, which pirate crews put to good use. Ironically, these periods of mass intoxication would last days or even weeks, alternating with periods of going without the most basic foodstuffs and water aboard ship, until landfall or the taking of another ship could replenish supplies.

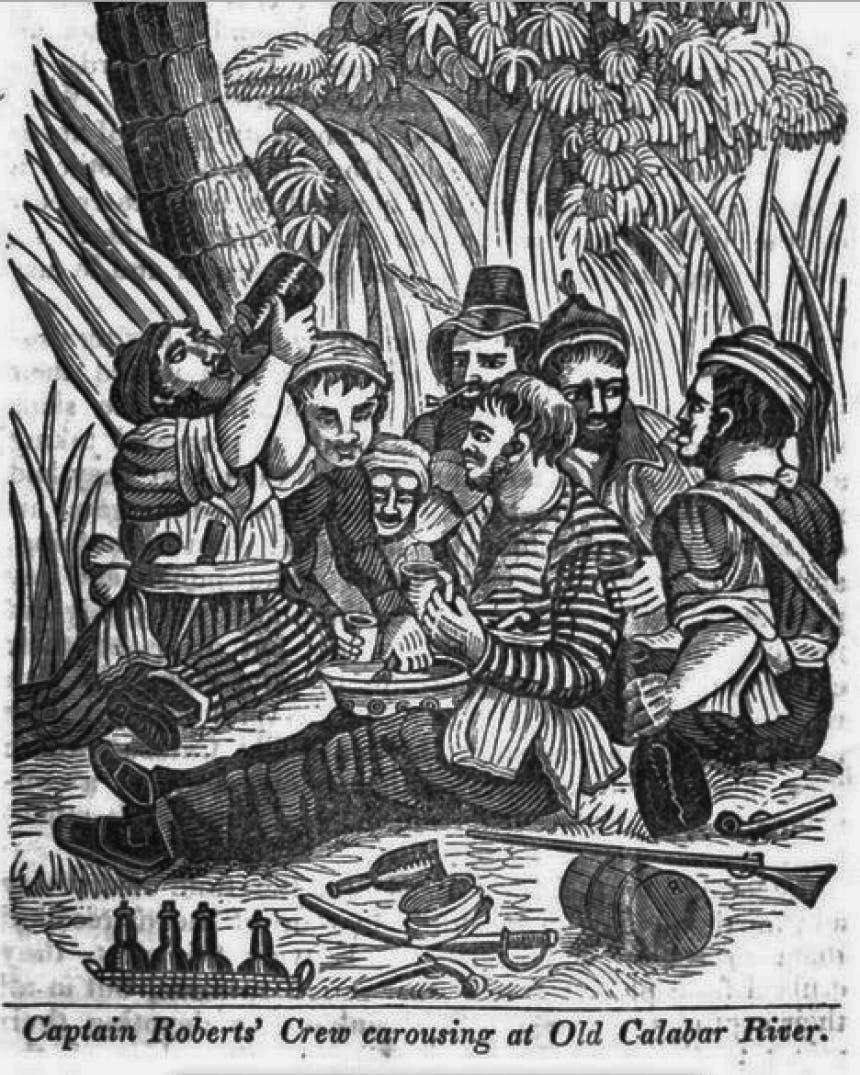

Another pirate, Captain Roberts, and his crew regarded themselves fortunate after taking several vessels circa 1720, where the cargo of liquor was “so plentiful, it was estimated a crime against Providence not to be constantly drunk.” Tales of Roberts and his crew relate that the ensuring celebration at a harbor near Old Calabar on the coast of Africa was a common occurrence, and in keeping with pirate custom, “the time of festivity and mirth was prolonged until the want of means recalled them to reason and exertion.”

Roberts was the epitome of a pirate of the day, from his rich crimson damask waistcoat and breeches to a red feather in his hat, gold chain around his neck, sword in hand, and two pistols hanging at the end of a silk sling flung over his shoulders. He had willingly joined the pirate ranks at an early age, and declared once in a drunken rage he would imprecate vengeance upon “the head of him who lived to wear a halter.” Roberts was killed not long after the visit to Old Calabar, during an engagement with a French man-of-war—shot through the throat with grapeshot.

In its “History of the Navy,” from the U.S. Navy’s The Bluejacket’s Manual (1959 edition), the section that describes war “Against the African Pirates” talks about how the fledgling navy of the United States at that time was basically saved as a service, owing to the need for its few ships (some 13 frigates) to be sent to the Mediterranean to thwart raiding Moorish pirates from the coasts. By the early 1800s, the North African pirates were no longer a threat to U.S. merchant shipping, while the U.S. Navy went on to fight the English next in the War of 1812. Nearly a century later, the new incoming Secretary of the Navy, Josephus Daniels, instituted “reforms” throughout the fleet, amongst these the decree that there would be no more drinking aboard ships. The Manual notes that some old-timers in the Navy received the news with “ill-concealed distaste.”

So goes the Navy saying “three sheets to the wind” when one is considered drunk. A “sheet” is a line that controls the sails on a ship; when it is loose, it flops around and control of the vessel is lost. Or, put another way, go ahead and have a “clap of thunder” (a strong alcoholic drink).