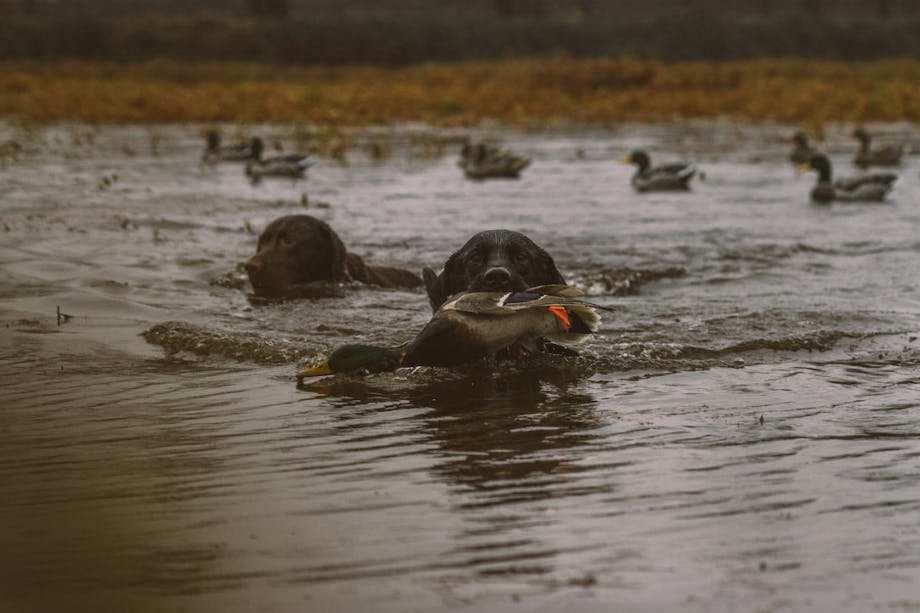

At the turn of the 20th century, sportsman John (Jack) Miner found himself amidst an unregulated commercial market, and local grassroots hunting. In the small town of Kingsville, Ontario, along the northern shore of Lake Erie, young Jack and his brother Ted spent their minimal free time carving and painting decoys in preparation for when the ducks would return. In Jack Miner’s memoir Jack Miner and the Birds (1923), he writes, “I had whittled in nearly every night of the winter, making a flock of decoys, and brother Ted did the painting.”

With North America experiencing rapid population expansion, there was a greater need for sources of meat, and so many people turned to market hunting to supply this demand. At that time, ducks and geese could be hunted year-round. Market hunting favored ways to hunt and trap ducks on a scale not previously seen before. Large punt guns mounted on boats were capable of shooting up to 40 or 50 ducks in a single shot and the invention of the pump and semi-automatic shotgun also increased the ability to shoot many more ducks than the previous muzzle-loaded shotguns.

"Now the first thing to consider is that over ninety percent of the people in America don't want to shoot. They want to see the birds alive. They take nothing from the shooter, but the shooter takes all from them. Which should control, the ninety percent, or the ten? I say there can be pleasure for both, if properly managed; but the shooter must be considered last, for the fall of one bird out of the air from his deadly aim gives pleasure to one only, while thousands are deprived of the thrilling enjoyment of seeing that bird alive.” (Miner, 147–148)

“We soon found that every grain of sport had vanished,” Miner explained, “and we were in a financial business. So, speaking from actual experience, I know that market hunting is not sport; that it is murder in the first degree, and no principled sportsman will practice it. For one successful market-hunter will deprive twenty-five real sportsman of their enjoyable recreation and outing.”

It wasn’t long before Miner and many others, including James Ford Bell, who was also an avid sportsman as well as president of General Mills (as well as the eventual founder of Delta Waterfowl), started noticing a decline in the number of birds. Miner recalls, “As I got older, ducks, like all migratory birds, got scarcer until I seldom ever went to hunt them. Yet I have always liked to see wild ducks, both on the table and in the air.”

“But the word sportsman spells a great many great words; first of all, it spells others and self-sacrifice, for to be a real sportsman one cannot stand alone.” (Miner, 172)

Slowly Miner’s speculation and concern began to gain traction among the general public as well. Miner states, “Every place I lectured, persons were asking, ‘What has become of our wild geese that used to come here by the tens of thousands? Where are they? Have they changed their migrating route or what has happened to them?’ I answered them by saying, ‘Automatic guns and systematic shooting is where they are migrating to.’ ”

In 1907, Miner dug his first spring water pond, which started him on the path to creating his famed wild goose sanctuary. Over time, he noticed that familiar ducks kept returning each year, but there was no way to be certain that they were the same ducks. So in 1909, he decided to make an aluminum tag to wrap around the ankle of one of his local pond ducks. It had the duck’s name and his address stamped on it.

“I am not opposed to a limited amount of shooting. I never was opposed to it. I am, however, absolutely opposed to ten percent of us exterminating what rightly and justly belongs to one hundred percent of us.” (Miner, 185)

In early 1910, Miner received a letter from a hunter who returned the tag and notified him that the duck had met its end. Over the next decade, Miner tagged hundreds of ducks and received letters from all around North America, from as far north as the Hudson Bay, to the southern tips of Florida and Louisiana. Essentially, he was mapping the first known migration routes.

But Miner’s love for ducks was dwarfed by his fascination with the Canada Goose. “Someone has said ‘the silly old goose.’ This to my mind, is one of the many demonstrations of how a man’s mouth can go off empty,” remarks Miner. “For the facts are that our Canada Goose has a great amount of knowledge, and many qualifications that the human race could well afford to profit by.”

Admiring their loyalty to family and partner, he observed many instances and documented many stories of the perceived valor and sense of duty of ganders and geese alike. In one instance, two ganders placed themselves between their family and an eagle. Watching them in awe, Miner remarks, “It was a great sight to see these faithful, self-sacrificing, old ganders at the head of their little bunch with their wings up, ready to strike, saying by their actions, ‘You must cut us down before you can have one of our loved ones.’”

It took Miner nearly seven years before he perfected a way to outwit, capture, and band them. Previously, his traps for ducks were easily foiled by the clever Canadas. In 1922, he finally got a trap that worked, and he banded hundreds the following year.

“But every place I lectured, persons were asking, ‘What has become of our wild geese that used to come here by the tens of thousands? Where are they? Have they changed their migrating route or what has happened to them?’ I answered them by saying, ‘Automatic guns and systematic shooting is where they are migrating to.’” (Miner, 237)

Suitably nicknamed Wild Goose Jack, he was foundational in the way information is collected on migrating waterfowl. His efforts set a precedence for the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. The act set limits on what time of year and how many waterfowl were allowed to be taken by hunting and inevitably led to population recovery over the subsequent years. Today, birds are banded in a similar fashion and efforts across the continent will forever owe thanks to Miner, who paved the way for modern waterfowl research and conservation.

“What will our children’s children think when they search our records and find that grandfather could lawfully shoot six tons of ducks and geese in one year?” (Miner, 238)

“Therefore, it is compulsory that we must work heart and hand together. But don’t let us use that word ‘compulsory.’ Let us say, lovingly together. Yes, for God’s sake and for the sake of the rising and unborn generations, let us work lovingly together.” (Miner, 236)