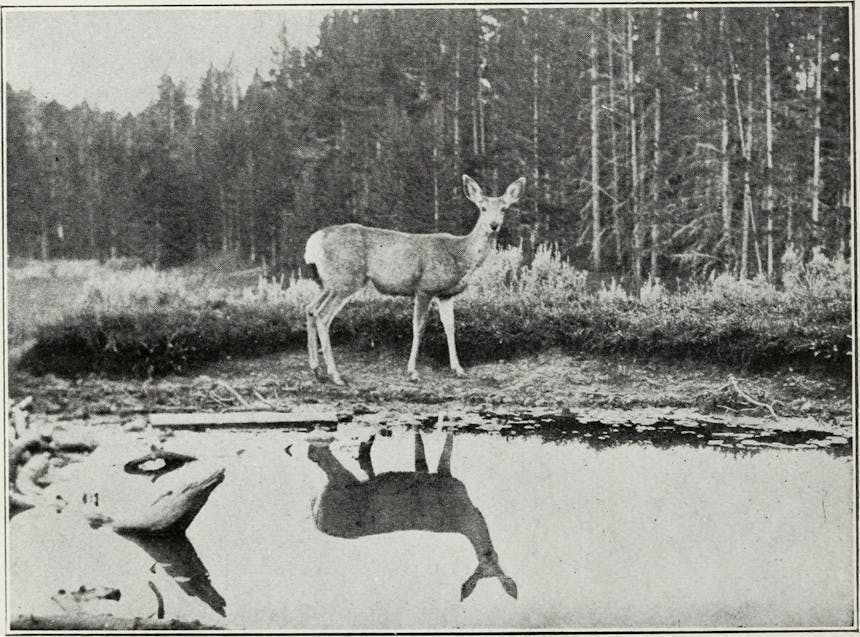

You probably don’t hunt in the Peach State, but your next deer encounter might have a connection to Athens, Georgia.

For about 50 years, students and faculty at the University of Georgia’s famous Deer Research Laboratory have conducted far-reaching studies across the country and beyond to improve our understanding of deer biology, behavior, and management. With an extensive list of published research and many graduates in high-ranking wildlife positions, the lab’s influence on the knowledge and management of deer is undeniable. But folks at the lab say the inspiration for their work goes beyond just a quest for scientific information.

“Deer are very close to my heart, and that’s mainly the research we do here,” said Dr. Gino D’Angelo, co-director of the lab. “We just want to see deer and wildlife be an important part of people’s lives.”

D’Angelo said the main purpose of the lab, housed at The Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources at the main University of Georgia campus, is to train future deer biologists and researchers. While the lab personnel focus mainly on white-tailed deer, often in the Southeast, their researchers have worked throughout the United States and in other countries.

The lab offers masters and doctorate programs and recruits students from across the country, often from traditional wildlife-management programs. Deer Lab students receive a full tuition waiver and are paid to complete their degrees. Basically, their research projects become 9-to-5 jobs. Also, the lab sometimes involves undergraduate students as technicians or volunteers and hires technicians in many areas to assist with research, capturing deer, or collecting data on habitat use.

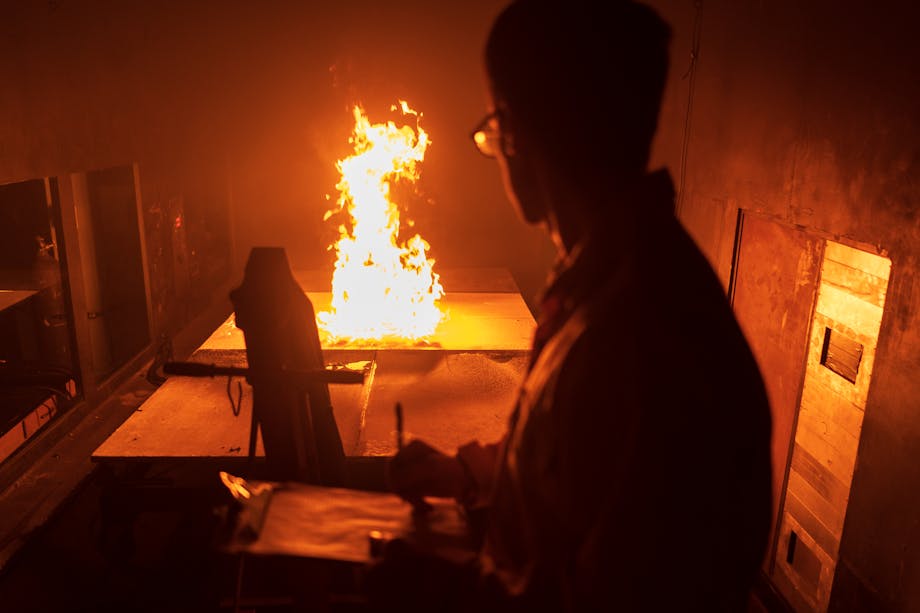

“We work on issues of deer-population management, learning more about the ecology of the species and how they relate to other species, habitat, and people,” D’Angelo said. “We’ve done a fair bit of sensory research—how deer hear, see, and sense the world. Really, we work on anything that kind of moves the ball forward on our understanding of deer.”

Often, the lab works directly with partners—such as the U.S. Forest Service, state natural-resource departments, or other academic deer-research programs—on projects. Previous studies have focused on deer vision, hearing, genetics, and diseases, plus antler physiology, habitat management, fertility control, scent communication, and reproductive behaviors, among other topics. Current efforts include a study on the use of GPS collars on fawns, research into coyote-caused fawn mortality in South Carolina, a multi-pronged field study of deer in the southern Appalachian Mountains of northern Georgia, and a Florida project in which deer at cattle ranches are captured, transported via helicopter, and collared so a student can study the habitat usage of bucks and explore better ways to survey deer for harvest estimates. D’Angelo said all studies are holistic, and students publish peer-reviewed results in professional scientific and wildlife-management journals.

“Graduates are trained and qualified to be on-the-ground biologists, researchers, or even administrators at state or federal agencies,” D’Angelo said. “Folks overseeing deer populations in the millions were trained here. We’ve also produced plenty of faculty: folks who are training the next crop of grad students at universities to become biologists and researchers of all sorts.”

The list of previous Deer Lab faculty, staff, and students reads like a who’s-who in whitetail management, including high-profile figures, such as biologist Grant Woods, Charles Killmaster of the Georgia DNR, and Brian Murphy of the Quality Deer Management Association.

Well-known deer researcher Dr. R. Larry Marchinton essentially started the lab in the late 1960s. D’Angelo now heads the lab along with co-director Dr. Karl V. Miller. David Osborn serves as research coordinator and also manages the lab’s Whitehall Deer Research facilities, about 10 minutes from campus. The number of students in the program varies. Currently, it has five masters and two doctorate candidates.

D’Angelo said deer enthusiasts often ask how they can become involved with the lab’s work. The facility has used volunteers, including hunters, to help with some projects. Further, people can stay up to date on the lab’s research via its website, which features sections on current news, and an information exchange, with recent publications and a research bibliography

“We spend a lot of time with outreach and extension,” he said. “We’re contacted by interested people with questions. We do our best to answer those questions and provide information.”

D’Angelo doesn’t see the lab’s work slowing down anytime soon. Even as the public’s knowledge of deer increases, questions constantly arise involving the place of deer and other wildlife in an increasingly complex landscape. The lab’s research and graduates will continue to help find answers.

“Deer are what we call a keystone species,” D’Angelo said. “They can change habitats, but they also interact so much with us humans. We’re trying to train people to try to optimize deer in the world, so they benefit the ecosystem and people.”