Both April 6, 1895 and August 17, 1896 stand out in the history of the Pacific Northwest and Alaska as the moments when miners prospecting along the Klondike River in Yukon Territory discovered gold from the sediment panned from those cold waters. From these initial discoveries, a torrent of fortune seekers would soon flood the Canadian wilderness.

There had been earlier gold rushes that spurred migration and economic activity across the nation: the California gold rush in 1848, followed by other bonanzas in southern Oregon and north-central Washington in the 1850s. Gold found in the Fraser River on British Columbia in 1858 created another mining boom across the U.S.-Canadian border, culminating with other mining booms in the 1860s throughout the newly-formed Idaho and Montana Territories. “Gold fever” spurred along mining industries, influxes of people, new businesses, and growth for west coast cities like San Francisco, Portland, Tacoma, and Seattle in the process.

By the time of these gold discoveries, Seattle was already on its way to becoming the major port on the West coast for accessing Alaska to the north and all other points west on the Pacific rim. Its population had grown from just 3,553 in 1880 to 65,000 by 1897. A new Northern Pacific spur railway line had effectively connected it to the rest of the country, and steamships plied the waters of Puget Sound daily, with this “mosquito fleet” of wooden-hulled ships supplementing other steamships that made regular passage north to the Klondike via ports in Skagway and Dyea.

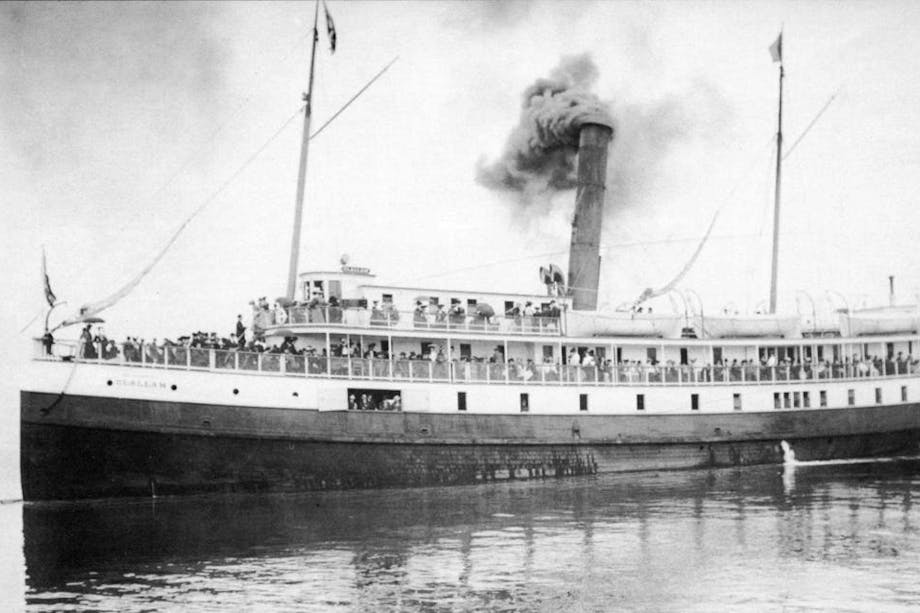

One of these steamers was the SS Portland. Nearly a year after the discovery of gold in Alaska, this ship brought news of it to…well, everyone else.

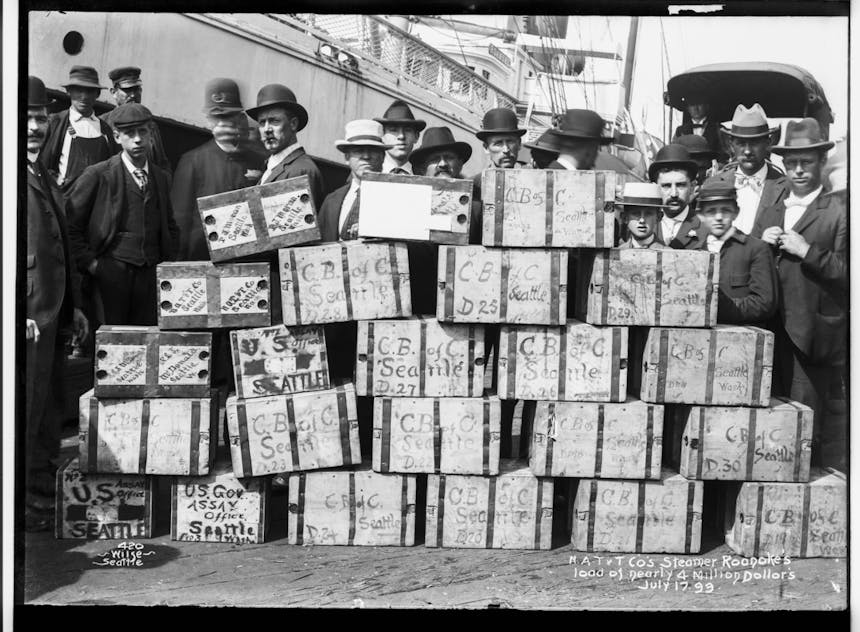

Cargo of gold at Seattle waterfront, July 17, 1899. Photo provided by: MOHAI / 1988.33.234

On a typical wet Northwest day, the Portland pulled into dockside in Seattle on the morning of July 17, 1897, arriving from St. Michael, Alaska, loaded with prospector gold deposits valued at the time at around $700,000. Only a few days before, another ship, the SS Excelsior, had made a similar voyage and pulled into San Francisco, also laden with $500,000 of gold from the far north.

The Portland’s arrival was nothing short of a bonanza. A staggering total weight of two tons of gold was unloaded before the day was done. Newspaper headlines of the day remarked that “sixty-eight men” had struck it rich, with “stacks of yellow metal”—a tale of fortune that spread like wildfire in the days and weeks that followed.

The offloading of passengers weighed down with sacks of gold took place at Schwabacher’s Dock at 6:00 a.m., as an estimated 5,000 people eagerly vied to catch a glimpse of the good fortune, as if it would rub off on them in the process. Joe Bergeoin, a former logger from Seattle, said he had $15,000 and was going back the next spring for more. Another passenger, John Wilkinson of Nanaimo, B.C., carried $25,000 in a leather sack whose handle snapped as he lifted it off the deck. Joseph Cazla of Montana carried $30,000 worth, and remarked to those watching that he drank up more than that in Dawson waiting to return south (of the 68 passengers aboard, 40 were later identified as miners).

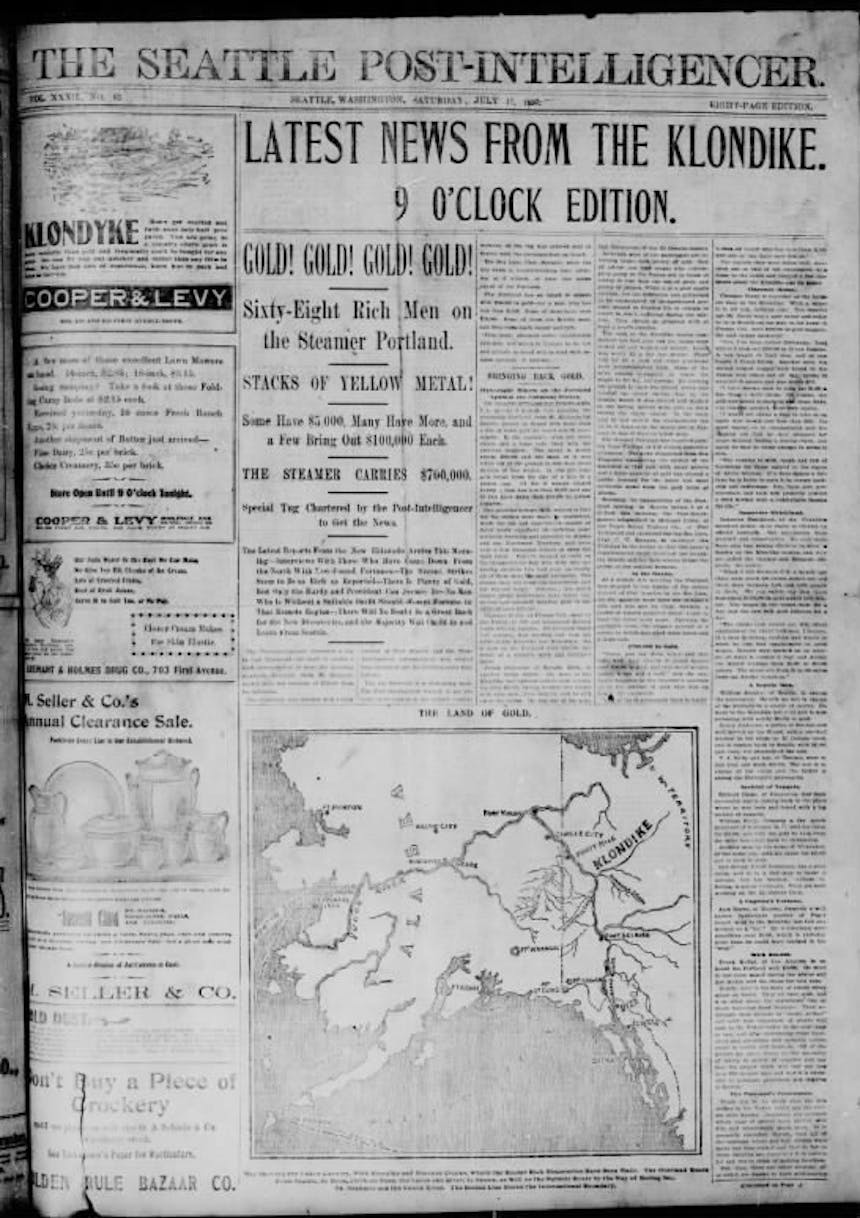

Front page of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer in 1897.

The city wasted no time capitalizing on the good news. In the coming days, the local Chamber of Commerce, under the direction of Erastus Brainerd, set out to actively promote Seattle as the “gateway to Alaska” and the gold rush that was soon to follow. According to historian Carlos Schwantes, a special edition of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer newspaper was issued with the story of the Portland’s arrival with gold and was distributed nationwide: 70,000 copies to postmasters, 15,000 to railroad hubs, 6,000 to public libraries, and another 4,000 to mayors. The announcement set the stage for the next expansion of Seattle’s commerce, transportation, industry, population, and services.

And come people did, in droves. Many arrived first in Seattle, looking to outfit themselves, if they had the insight to plan and prepare for the journey in advance. Merchants such as Clinton C. Filson, who had first come to the city in 1890, offered a variety of durable cold weather clothing and goods to outfit these gold seekers. A year after Filson opened his company in Seattle, a newspaper illustration titled “your life may depend on your outfit” highlighted the need to have good equipment just to survive in the north: on one side of a mountain pass, skeletons and upturned sleds frozen in the snow were marked with the sign “Victims of Cheap Outfitters,” while those on the right, marching along in parkas and making progress along the trail, were noted as being the “Result of Proper Outfitting.”

C.C. Filson store on 1st & Madison, Seattle, Washington, 1905. Photo provided by: MOHAI / 1983.10.7063

In 1898, Filson operated its stores at 1119 First Avenue and at the corner of Occidental and Yesler avenues. Called the Seattle Woolen Manufacturing Company, Pioneer Alaska Clothing and Blanket Manufacturers, the operation not only sold but also manufactured mackinaw clothing, mackinaw blankets, and knit goods, as well as boots, shoes, moccasins, and sleeping bags specially designed for the frigid north. Many prospectors came to the Filson company as a reliable source for their preparations, including Robert McFadden. A handwritten list given to McFadden in 1898 by an unidentified authority on the Klondike offers recommendations for what types of clothing McFadden should outfit himself with before attempting the journey to the north to prospect gold, and details why these items were all must-haves. Among those listed are several from Filson’s store, along with their prices: a pair of leather mitts (fifty cents), one sweater (eight dollars), two pairs of woolen mitts (one dollar), and one Cruiser shirt for five dollars.

Besides the journey to get there, self-proclaimed prospectors faced labor that many were unaccustomed to once they reached their destination in the Klondike. Gold could be removed from gravel deposits in creek beds using the panning method; however, this was a time-consuming process, and experienced miners used it primarily for sampling deposits. For more efficient prospecting, other tools, such as a shovel, pick, and rocker/sluice box, were employed to extract the precious metal. Water was often a key ingredient in this process, used with the sluices when available. Provisions like tents and snowshoes, and basic staples such as coffee, bacon, flour, beans, and sugar were more money to be spent and more weight to be carried. Added to these were the cost of pack mules and horses to haul everything over the passes and back to Alaskan ports; 3,000 of them died along the trails suffering from neglect, starvation, and overburden.

U.S.-Canada border on the Chilkoot Pass, 1898.

An estimated 100,000 prospectors attempted to travel north—a two-month journey—first by water (there were no overland roads or rail lines leading north), then over the deadly White Pass Trail from the port at Skagway, or the equally dangerous Chilkoot Pass Trail from Dyea, or the Edmonton Trail, advertised as the “back door to the Yukon.” In the 24 hours after the Portland’s docking, 2,000 New York residents attempted to buy tickets for the Klondike aboard the steamer SS Queen, unsuccessfully because locals had already bought them. In the days following the nationwide announcement of the discovery of gold, other steamships bound for the north quickly sold out of tickets for passage as people called “stampeders” sought to be the first to reach the gold. Within 10 days, 1,500 persons departed Seattle for the goldfields.

One stampeder, B.E. Axe, gave voice to what many were no doubt thinking as they made their way north: “I am going to succeed, you bet! And this success will enable me to give my family a better home.”

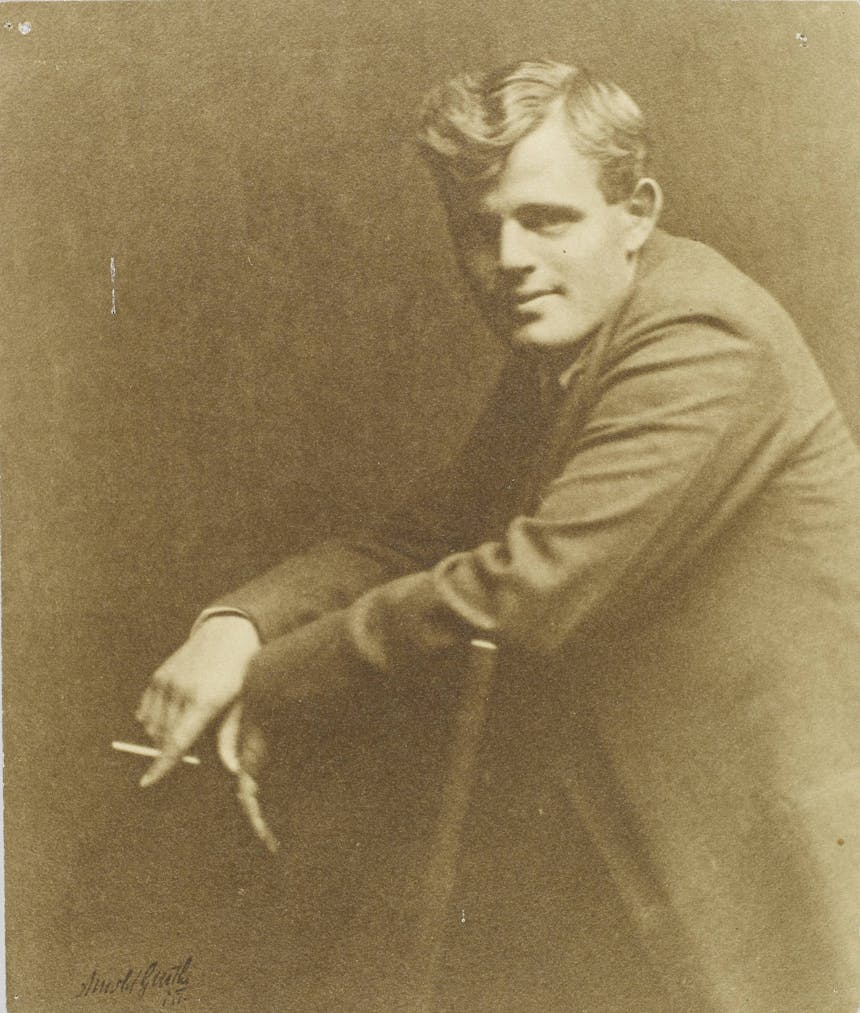

Portrait of Jack London from side, he leans over back of chair with cigarette in hand.

Another of the very first of these 100,000 seeking gold was Jack London. He made his fortune in the Klondike, but in a different way. While many who traveled north to the goldfields looking for riches came away bust from the experience (or not at all, having lost their lives along with their livelihoods), London used his time in the far north to harness his creative writing ability. Of his time there, he reflected, “It was in the Klondike that I found myself. There you get your perspective” (Jack London by Himself).

With the financial backing of his brother-in-law and co-traveler, Captain James Shepard, London made his initial trip from Juneau in an Indian canoe instead of a ship, enabling his party to land safely, and prepared for the next phase over the mountains to the Klondike. He wrote to Mabel Appelgarth from the port at Dyea while waiting to embark on the Chilkoot Pass Trail:

I am laying on the grass in sight of a score of glaciers, yet the slight exertion of writing causes me to sweat prodigiously.

We lay several days in Juneau, then hired canoes & paddled 100 miles to our present quarters.

The [native people] with us brought along their [wives], [children], & dogs. Had a pleasant time. Am certain we will reach the lake in 30 days…

"Front Street, Sheep Camp. c1897" Depicts Jack London and fellow travelers Jim Goodman, Fred Thompson and Martin Tarwater.

On August 21, a 21-year-old London posed with a group of miners at Sheep Camp for visiting photographer Frank La Roche. La Roche’s photo is the only known picture of the author in the far north, and a visual testimony to the experiences that led to his signature novel Call of the Wild and a score of other works (such as his story “Which Make Men Remember,” and his first novel, A Daughter of the Snows) that have the Klondike as their backdrop and formulative experience.

The Klondike Gold Rush lasted just a short time. By early 1899, goldfields in the Klondike were controlled by corporate syndicates and individual prospectors had shifted their attention elsewhere in Alaska. The SS Portland was wrecked at Katalla, in Alaska, on November 12, 1910. But its place is solidified in the history of Seattle and Alaska for the gold rush it helped to usher in for many in the Pacific Northwest and beyond.