When you meet Zech Bennett, he seems like a pretty ordinary guy. Not too tall or too short, he seems somewhat in shape but is not a chiseled gym rat. The brown hair sticking out from underneath his baseball cap is slightly askew, and his face breaks into an easy smile. He is the type of person you could share a few beers with at the bar while swapping stories about ferrying kids to events or catching up on the latest scores. It’s only when you hear what the 32-year-old Homer, Alaska, resident does for a living that you realize there is more to him than you see at first glance.

As an underwater welder and salvage diver, Bennett routinely slips under the surface of the roiling seas, glacially silted streams, and frigid cold bays of Alaska to repair ships and bring up wrecks off the bottom.

Born and raised in Paradise Valley, Montana, Bennett spent his time roaming the woods and wilderness surrounding his home as a child. The idea that he would forge a career working underwater could not have been further from his mind. He had never even seen the ocean. While working in a sawmill in his early twenties, Bennett decided to try his hand at welding, a job his father also did. He took to it. Soon, the lure of better money drew him to Seattle, where he learned how to underwater weld. Not too long after that, he headed north. “I always loved being in the outdoors and making my own way, maybe that’s what ultimately led me to Alaska,” says Bennett. “Hell, I don’t know, but I love it here!”

In a state as vast as Alaska, with over 6,640 miles of coastline―more than the rest of the United States combined―and 86,051 square miles of inland waters, people who work on or under the water are always in demand. Large fishing fleets ply the waters, a thriving oil industry needs welders of all sorts, and the remoteness of the state requires individuals who can bring solutions to far-flung problems. From oil wells in Prudhoe Bay way above the Arctic Circle to sunken skiffs down south, when there is an issue to be solved underwater, Bennett is usually the first one people call.

Since he first became certified (he now has more certifications than he can count) in 2010, he has logged over 25,000 hours underwater working on a variety of issues. One of the biggest skills he has learned is how to think on his feet when he is down and to not lose his cool, no matter how challenging the situation. When a 175-foot ship has fouled its prop and can’t head back out to sea, every minute it’s at dock is money lost, money that the owners don’t want to lose. So when they call Bennett in, they expect him to get to work immediately.

"I don’t think I am that special. I just do a job that needs to be done. Granted, I do love it. I love the freedom of being able to call my own shots and being the guy with the answers. The guy that can solve the problem that most people can’t."

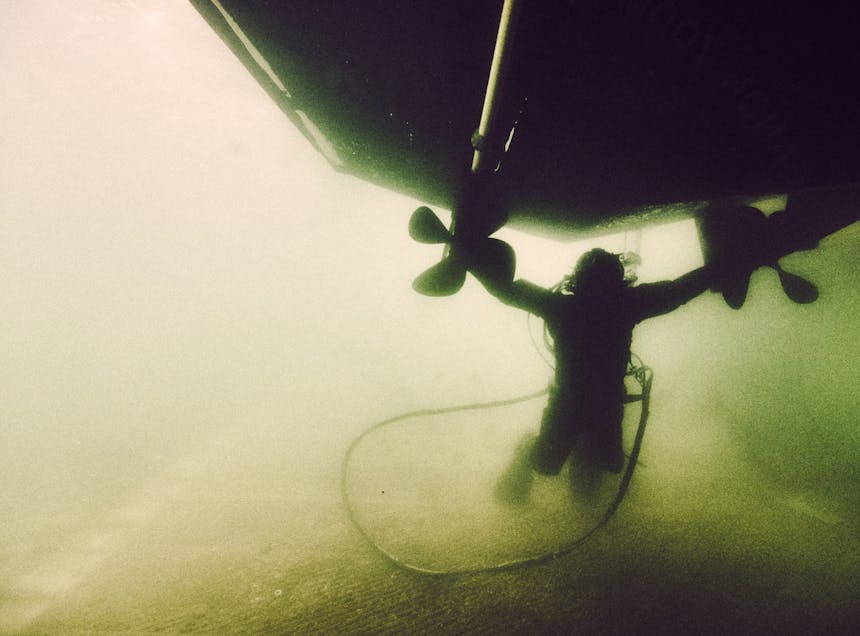

“The town of Nikiski, on the Kenai Peninsula, on its best day is the worst water in the world to dive. The moment you go under, it’s like diving in tar; it’s so black, you can’t even see your hand in front of your face. Couple that with a steady current by the docks that wants to blow you away, and it’s challenging to say the least. I had to dive there a little bit ago in a storm to clear out a Z-drive prop, and the ship was bobbing around like a toy in a bathtub. I timed my descent with its motion and followed the hull with my hands until I found the prop. Then I wedged myself in and cut away all of the line that was tangling it up. It took several hours, but we got it cleaned up, and she went on her way,” says Bennett.

The key to pulling off a dive like this, or simpler ones, is to have the right gear and to work with proven systems to ensure safety. All of Bennett’s gear is checked daily, both before and after every single dive. When he dons the dive helmet and connects his umbilical cord to the surface, he knows that he has two sources of air, that he has working coms to reach the surface, that none of his equipment is in danger of failure. His tender on the surface is in constant communication with him to ensure nothing goes wrong. A successful dive, no matter how easy, is the result of careful planning and preparation.

His favorite job is raising sunken ships. From the moment he gets a call, his mind starts spinning. He and his team conduct multiple dives to see how the boat is sitting on the bottom and what hazards there are. Is there a current, how are the water conditions, is visibility good, how deep is it? Once he has that info, he pairs it with the physical information about the boat—what it’s made of, its overall weight, what cargo it was carrying. Then he develops a game plan for bringing it back up. “Nothing is more gratifying than seeing a large boat break the surface and knowing that we got it there,” he says.

When asked what he thinks about what he does, he just shrugs and smiles. “I don’t think I am that special. I just do a job that needs to be done. Granted, I do love it. I love the freedom of being able to call my own shots and being the guy with the answers. The guy that can solve the problem that most people can’t.”