HAZARDOUS WEATHER CONDITIONS. SMALL CRAFT ADVISORY. STRONG WIND WARNING IN EFFECT.

These are common warnings to mariners who may be considering the Strait of Juan de Fuca—the passage running between the south end of Vancouver Island, BC and the north coast of the Olympic Peninsula of Washington State—during the fall storm season of 2019.

What is true about this maritime transport corridor today has held true for the same region for over 200 years. Those who would ignore or downplay such warnings do so at their peril.

Ships ranging from die-hard fishing vessels and ocean-bound cargo ships, to passenger steamships and ferries have long braved these waters en route to Alaska and other points north, or heading south once out of the western end of the passage on the way to ports along the western seaboard or further into the Pacific Ocean. The waters of the Strait offer cold comfort to anyone unprepared or unlucky enough to find themselves at their mercy: the average temperature of the water along the coast and in the Strait of Juan de Fuca ranges from 45 degrees Fahrenheit in January to 53 degrees Fahrenheit in July.

Not all who have plied this passage in the past have been fortunate. The weather of the Pacific Northwest coastal areas can try the best ships and crews. The maritime history of the state offers a sobering record of ships lost over the past 200 years—sometimes, without a trace.

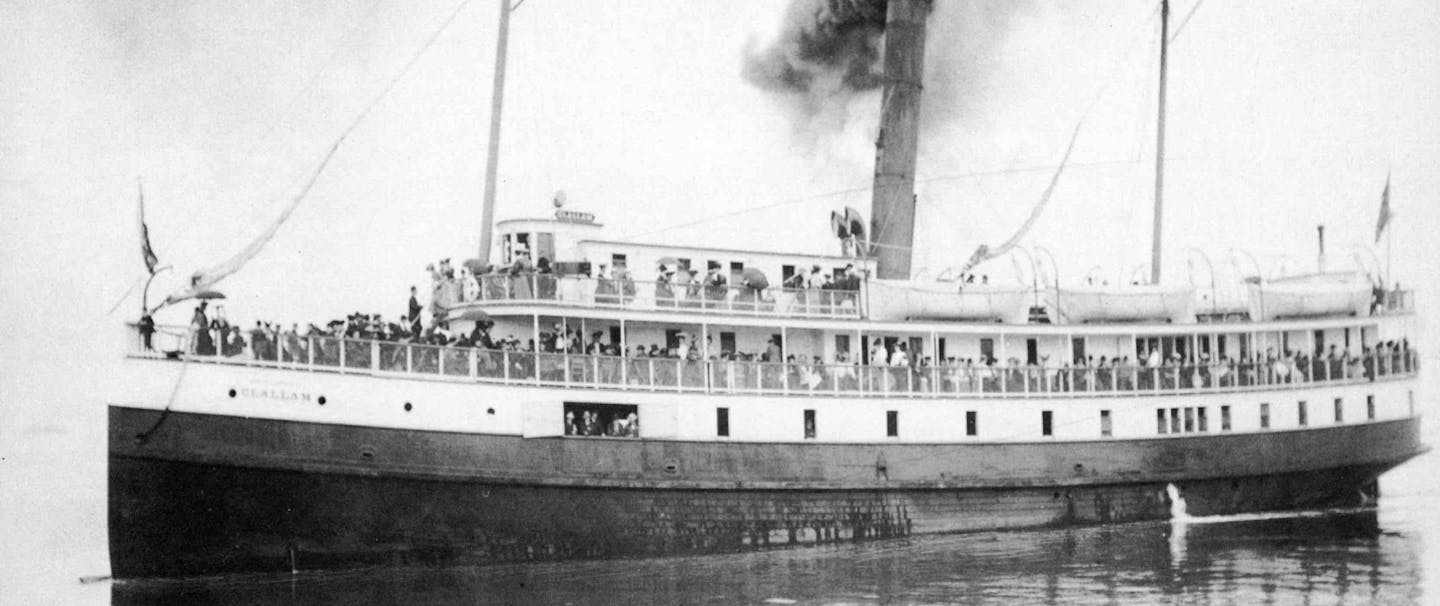

One of these cautionary tales concerns a steamship at the turn of the last century: the steamer SS Clallam, launched in Tacoma in 1903 for the Puget Sound Navigation Company. The ship was a passenger vessel, intended for regular runs between Tacoma, Seattle, Port Townsend, and Victoria, BC—the latter extent of its transit taking it out of the inland waters of Puget Sound and through the notoriously treacherous Juan de Fuca Strait. It was just a year after her launch that the Clallam and many of her passengers and crew suffered a tragic fate in these waters.

On January 8, 1904, the Clallam, under the command of Captain George Roberts, departed Tacoma on a northbound voyage, with Victoria as the final port of call. The first part of her journey was a typical run, with stops made in Seattle and Port Townsend to deliver goods and pick up new passengers. By the time the ship pulled away from the dock in Port Townsend at 12:15 pm, she carried 61 passengers and 31 crew.

While underway to Victoria, the winds and waves picked up across the Strait. The weather steadily worsened, with winds reaching an estimated 36 mph. By 5:00 pm, the ship was seen off Trial Island near the Canadian coast, rolling in the waves.

The tale of those aboard ship was later documented by the survivors. As the ship made its passage into the rising storm gale, a faulty deadlight (a strong shutter or plate fastened over a ship’s porthole or cabin window in stormy weather) had buckled under the pounding waves on the hull. Rising water in the engine room greeted the ship’s chief engineer, Scott DeLaunay, when he went to investigate. By 3:00 pm, both the ship’s main bilge pumps and its backup pumps had failed, and the water put out the boiler fire, leaving the ship adrift without power.

Fearing the worst as the ship continued to take on water, the Captain ordered lifeboats lowered at 3:30 pm, with orders for women and children to be loaded aboard the boats first. It was a disastrous decision, compounded by the failure to include ship’s officers in any of the lifeboats.

“It serves as a stark reminder to the hubris of seafarers and the wrath that can befall those who brave the oceans of the world.”

All three of the lifeboats launched either were destroyed while being lowered on their davits or capsized in the heavy waves once free of the ship. Those still aboard watched helplessly as their wives and children perished under the waves. All told, 56 of the people in these lifeboats drowned, 45 of them passengers: not one of the 17 women and 4 children survived. Other estimates place the loss of children even higher, owing to the fact some were below fare age and therefore not recorded in the official passenger manifest.

Those remaining on the Clallam, including Captain Roberts, were able to keep the ship afloat by bailing with buckets. Their dire predicament was worsened by the fact that signal distress flares were nowhere to be found, despite this being a requirement within maritime law. By the early morning of January 9, the ship was finally located and taken in tow by the steam tug Richard Holyoke, which pulled the vessel eastward toward San Juan Island and safety.

However, it was not to be. At 1:15 am, the Clallam foundered and sank, nearly taking the tug with it in the process. The tug crews of the Richard Holyoke and another tug, the Sea Lion, rescued most of the 36 remaining passengers and crew from the icy waters.

Vessels lost at sea are often subject to human beliefs and superstitions about the maritime environment, and the Clallam was no exception. At its launching, the bottle of champagne used to strike the bow of the ship failed to break, while the American flag attached to its mast lanyard unfurled upside down: both were taken as ill omens for the ship. And on the day of its final voyage, one of the animals taken on board, a “bell sheep” (so called for the bell affixed to its collar), refused to board the Clallam at the Seattle stop, and was seen by many as a sign of bad luck.

The loss of the Clallam led to a formal inquiry of the captain and chief engineer, with the suspension and revocation of their maritime licenses, respectively. The choice to launch the lifeboats without adequate seamen in all of them, and in rough seas, weighed heavily in reports about the sinking. An official maritime report of the disaster issued February 13, 1904 concluded that the ship was flooded by open bilge and sea cocks, which extinguished the boiler room fires and resulted in the loss of power to the ship. The ship’s shoddy state of repair and lack of working pumps and flares may also have contributed to the disaster. New inspections soon followed for other steamships that took over the Clallam’s regular service route.

The hulk of the Clallam was salvaged, but later abandoned on the shore of Oak Bay in June 1904. To this day, it remains the greatest maritime disaster involving a Puget Sound Mosquito Fleet steamer in the Pacific Northwest. It serves as a stark reminder to the hubris of seafarers and the wrath that can befall those who brave the oceans of the world.