The true pioneer era in Homer, Alaska ended in 1978.

An old homesteader once told Kate Mitchell, “That was about the year you figured you weren’t going to starve to death.” By then, much of the community enjoyed wanton luxuries like electricity and indoor plumbing. That was also the year Kate moved to Homer.

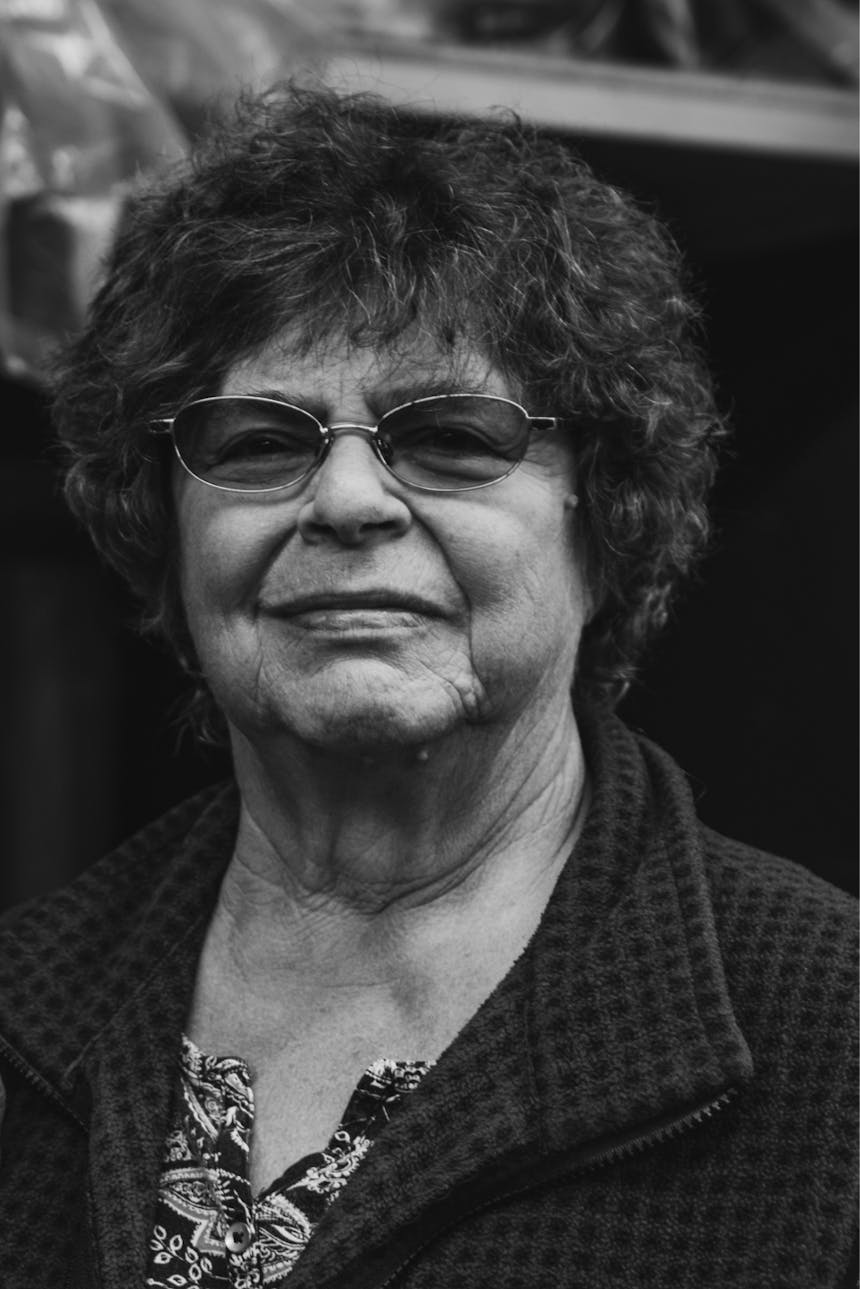

However, just because she missed the “true pioneer era” doesn’t mean she didn’t blaze a few trails. Quite the opposite. Kate built NOMAR by designing and sewing innovative products that dramatically improved the quality of salmon that Alaskan fishermen exported and made fishing a little safer and easier. She did so by pouring out love and support to a community that actively rejected her at first.

Most people nowadays think of sewing as an activity their grandma does, patching holes in jeans or making blankets for grandchildren. But commercial sewing is an important industrial trade, one that has largely been lost or moved overseas in the last half century, which makes NOMAR’s story even more unlikely. Though it has evolved with technological changes, it still requires a steady hand, a skilled eye, and hundreds of hours of practice to master.

Kate inherited a legacy of commercial sewing—and perseverance—from her mother, Ruby.

Ruby, born in 1910, had dreams of going to business school, but her parents forbade her. During World War II, she saw an opportunity to enter the workforce by responding to Christianson Upholstery’s newspaper ad after many of their workers were drafted to fight in Europe and the Pacific. The company’s owner, skeptical of hiring women, challenged her to lift a couch up on some sawhorses single-handedly. She succeeded.

The owner grew so fond of Ruby that he recommended her for her journeyman card in the upholsterer’s union just eighteen months after she was hired, making her the first woman to join the upholsterer’s union in Washington state. Twelve men came from the union hall to stand around all day, watch, and criticize her work, but they couldn’t keep her from receiving her card.

After the war, Ruby left the workforce to take care of the farm and her newborn—Kate. Ruby raised Kate to be hardworking and enterprising, teaching her to raise chickens and sell the eggs to neighbors. She lied to a local berry farmer about Kate’s age so she could work picking berries in the summer. At age twelve, Kate picked a hundred pounds of berries a day and was crowned the farm champ.

She graduated from high school with a secretarial certificate and awful timing. Boeing laid off 9,000 skilled office workers in Washington in 1964. A high school graduate with no experience had little chance of finding office work anywhere. When Kate heard a radio ad stating that the Coast Guard was recruiting women, she joined up.

Kate left the reserves to have children in the mid-1970s while her husband was stationed in Ketchikan, where serendipity led her to start plying her trade in the Alaskan marine industry.

First, she found an old commercial sewing machine at the Coast Guard. Right around the same time, the local canvas woman hurt her back and one of the other “coasties” was looking for a boat top. Kate gave it a try for some extra dollars in her pocket, and word soon got around that she did boat tops. In a town of hundreds of boats, 160 inches of annual rainfall, and no local canvas maker, Kate had a plethora of opportunities to cut her teeth on.

By the time the Coast Guard transferred her husband to Homer in 1978, she had established herself as a capable canvas maker. With twenty-four months of paychecks left until her husband retired, she was determined to establish a business steady enough to support him and the family in his transition from the military to the civilian workforce.

However, in Homer Kate found a different business environment than in Ketchikan. Homer was smaller, and the locals didn’t trust the Coast Guard personnel floating in and out of town. They wouldn’t even give Kate a chance to set up shop. “I couldn’t find any space to rent,” she said. “We were military, seen as temporary and not necessarily trustworthy.”

She turned to advice she’d received years ago from her mother, who had also attempted to ply her trade among a hostile audience. “You can accomplish anything you want to,” Ruby told her. “You simply have to outlast the bastards trying to stop you.”

Kate decided she didn’t need a shop. She scraped the money together and bought an old GMC school bus and slapped “Mitchell’s Marine Canvas” in big white letters on the side.

Commercial fishermen were the first to discover her. “They didn’t care I was in this funky school bus. I had a sewing machine and I knew how to use it, and that was good enough.” By the fall of 1979, business was good enough to move to a building of sorts. “We moved out of a school bus into a dirt-floor Quonset hut with a coal-burning stove,” she said, “and that was a step in the right direction.”

“You simply have to outlast

the bastards trying to stop you.”

Three years later, in 1982, two fishermen came to Kate with a challenge so pressing that it would revolutionize the way Alaskan fishermen stored and delivered salmon and force Kate to hire a dozen workers and change the company name. “Winter of ‘82,” Kate says, “something great happened but, of course, there was no knowing it at that time.”

These fishermen had an issue. They were gillnetters targeting sockeye, a high-value species of Pacific salmon. After they worked so hard to catch the fish in Prince William Sound or Cook Inlet or Bristol Bay, they would store them in bags made of seine web and take them back to town to deliver to the markets.

The problem with the seine web is that it’s a thick, loose, knotty fishing web. When you dumped 1,000 pounds of sockeye into a bag, the weight of the fish would press a significant portion of the catch into the webbing and bruise the flesh of many of the fish. Then in town, the market would sort the fish, and though the perfect specimens were bound for fillets and fish markets all over the country, the fish with bruises and marks were destined for cans on supermarket shelves.

If Kate could develop some kind of industrial-strength bag that would hold their catch gently and provide the necessary drainage, they could deliver more perfect specimens and make significantly more money, sometimes double the price per pound.

Kate’s journey took years of finding the proper industrial mesh, the right size and shape, and developing a strong sewing technique. By the summer of 1984, she had perfected the design after several iterations and trademarked a name—“NOMAR,” meaning “no marka the fish.”

Word spread quickly, once again, about Kate Mitchell’s sewing talents. The crew of the tender F/V Gandle from Cordova, a thoroughbred commercial fishing town across Prince William Sound, was in Homer taking deliveries of salmon. They watched how quickly the Homer fishermen delivered silvers in the NOMAR brailer bag at the Homer docks and how well the bags preserved the integrity of the meat. They spread word of this innovation to the Copper River Fisherman’s Co-op, a group of a hundred Cordova fishermen who were working to increase the quality of their fish and the return on their investment.

The Co-op moved fast by voting that fall to buy salmon delivered only in the NOMAR brailer bag. They placed an order for five hundred bags to be manufactured over the winter and delivered in the spring of 1985.

That was just the start. The brailer bags were a hit and became the industry standard over the next decade. Competitors popped up and dropped out quicker than a summer salmon run. They would undercut NOMAR’s price, but could never match the quality of the product. NOMAR’s bags cost hundreds of dollars, but a bag that broke and spilled fish would cost a fisherman thousands. NOMAR remained the gold standard in brailer bags—becoming an Alaskan household name, like Kleenex.

After that first order of five hundred bags for the Co-op, she had to lay off her entire winter staff in the spring, and it broke her heart. She figured if she had enough business, she could become one of the few companies that allowed people to make a living year-round in Homer instead of profiting off short, intense summers in the tourism or commercial fishing business and then scraping by through the winter.

With the goal of supporting her employees, Kate listened closely to the fishermen who came to her and made it her mission to solve their problems. “It’s the commercial fish that opened doors in a lot of different directions,” she said.

“Something great happened but, of course, there was no knowing it at that time.”

Could she rework Patagonia’s secretive and wildly expensive Polar Fleece jackets into simple sweats for working Alaska’s frigid waters? Could she build a better “chew bag” that pot fishers could drop to the ocean floor and withstand the onslaught of crab and black cod picking at the contents? Yes and yes.

Overall, she says, Kate built NOMAR to serve. To serve the fishermen, to serve her employees, and to serve her community.

“People love Homer. I mean, it’s a beautiful spot. If everyone who came got to stay, we’d probably be at a couple million people. Because you have to be so tough and willing to take a lower level [lifestyle] than what you think you should . . . you have to give up keeping up with the Joneses and be content to live. And not so intrinsically set on building this empire but building a community.”