Between Seattle and Chicago, a train called the Empire Builder rolls on 2,206 miles of steel track. It leaves daily on a 48-hour trip, gliding past splendid vistas including Glacier National Park. However, possibly its greatest feat lies beneath the surface.

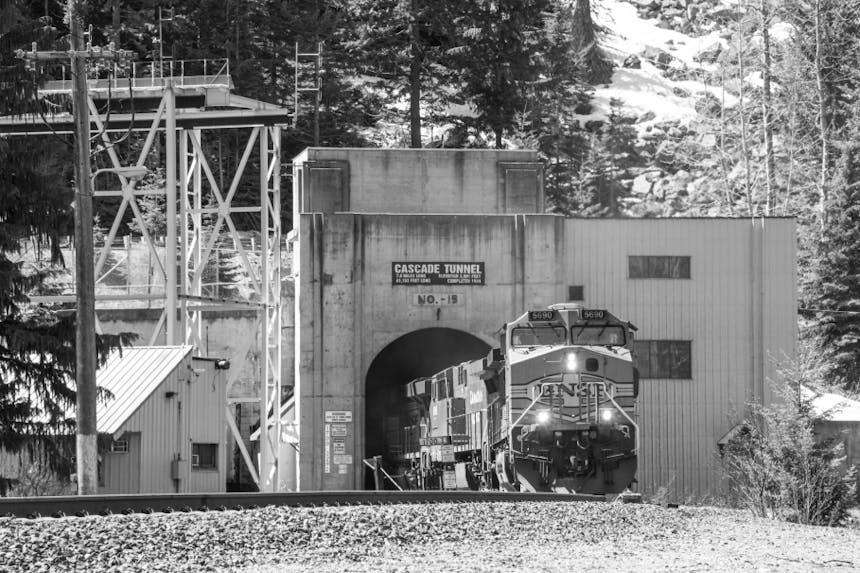

Underneath Stevens Pass on the east side of the Cascade Mountains of the state of Washington lies a concrete portal. Red-and-white-checkered steel doors large enough for a locomotive to pass through open to reveal a hole cut through 7.8 miles of granite. This is the Cascade Tunnel. When first built, it was the longest tunnel in the western hemisphere. Today it remains the longest tunnel in the lower 48 states. Its location obscured and humbled by a century of megaprojects, this exploit remains mostly unremembered.

In the 19th century, railroads became much of the economic and industrial sinew that thrust the United States from a frontier backwater to a 20th-century superpower. Although passenger numbers have declined significantly since the 1950s, freight traffic continues to grow into the 21st century. When it comes to moving anything large and heavy over vast tracts of land, the railroad remains king.

Marion Shovel Mill Creek. Courtesy: Great Northern Railway Historical Society

Inspiration for the tunnel came from a short, grizzly, one-eyed Canadian American named James J. Hill. During a career in steamboat shipping in Minneapolis and St. Paul, he saw the future in trains and began buying struggling railroads that would form the Great Northern Railway. He would become a Gilded Age peer of J.D. Rockefeller and J.P. Morgan. By the time of his death, the president of Great Northern was known as “The Empire Builder.”

Hill’s railroad was not the first to connect the Northwest with the Midwest, but his was the most efficient. He was fanatical about building the flattest, straightest line with the best materials. It cost more up front, but he could maintain speed and reliability and thus remain profitable at lower rates—a feat his competitors could not match.

Hill was hands-on and detail-obsessed, often examining his rail in person. During a blizzard, he became frustrated at the flagging effort of his crew to dig them out. Stepping from his luxuriously appointed private train car, he joined them. Taking a shovel from an employee, he sent his men in one at a time to his heated personal car to drink hot coffee while he continued digging.

GE Motor 4 miles underground. Courtesy: Great Northern Railway Historical Society

Competitors had reached the city of Tacoma on the Puget Sound years before. Hill demanded the Great Northern Railway have its own line to the timber, coal, and deep-water ports. Between him and this prize were the steep snowcapped stone walls of the Cascade Mountains.

To find his own route through these peaks, a locating engineer named John Frank Stevens—a man described as “impervious to climate”—was hired. In 1890 one of Stevens’s team surveyed an obscure tributary of the Wenatchee River. Stevens looked for it himself and found the brutal pass that now bears his name.

It would take 40 years to force the mountains to submit to the Great Northern timetable. By 1893 the interim track was completed—just long enough to establish service to the Puget Sound with a set of eight terrifying switchbacks. In 1897 the first Cascade Tunnel of 2.6 miles began construction and was finished three years later.

Snow was the natural enemy of the Great Northern, and the battle was fought seven months of the year. Protective snow sheds were built along the line to protect the trains from avalanches. Combined with snowplows, this was plenty to handle a typical winter, but 1910 was not normal. A ten-day blizzard in February stopped two trains at the pass. The slope above had been denuded of vegetation the summer before, leaving a smooth chute towards the tracks. The weather changed and warm rain began to fall. Lightning struck and unleashed an avalanche. It washed the trains into the valley, killing 96 people. Five months later, the last body was found. It remains the deadliest avalanche in United States history. By the following year, Great Northern installed eight more miles of snow shed over 12 miles of track.

It soon became clear the cost of maintaining the snow sheds was prohibitive. A longer tunnel was needed. Hill died in 1916 and Great Northern was continued by his son. By 1925 they were ready to attempt a second tunnel. It would be a lower elevation and over twice the length of the first. Company towns sprang up on either side of the mountain, and an army of 1,793 men began to work around the clock.

Left - Workers loading dynamite / Right - Breaking through the New Cascade Tunnel. Courtesy: Great Northern Railway Historical Society

Speed was paramount. The goal was to build the tunnel in three years—twice as fast as any prior tunnel project. Workers dug a small “pioneer” tunnel parallel to the main tunnel. This allowed multiple shafts into the side of what would become the tunnel and opened up several fronts, letting workers blast their way in several locations.

Though safety was said to be a priority, there were several deaths from blasting and collapse. A report by the Washington State Department of Labor and Industry determined that “all possible safety measures” had been taken and deemed the deaths accidental. The King County Coroner determined there would be no inquest. He concluded that “During construction of the tunnel, these things have occurred with great frequency.” Incidental deaths were to be the price of this enormous hole.

Drawn on a topography map of the Cascades, the 2.6 mile and the 8-mile Cascade Tunnels are illustrated. Courtesy: Great Northern Railway Historical Society

When the east and west ends of the tunnel finally met under Stevens Pass, their alignment was off by a single foot. Workers lined the jagged walls with nearly three feet of concrete. The new line eliminated 11 miles of tunnels and snow sheds and dropped the maximum elevation of the line by 500 feet.

On January 12, 1929, during a special nationwide broadcast, the newly created National Broadcasting Company (NBC) presented the dedication of the Cascade Tunnel with dignitaries and celebrities, including a speech by President Herbert Hoover, over the radio. Two days later, NBC’s wild west variety radio show “Empire Builder,” sponsored by Great Northern, began the first of 103 episodes to promote the line. The first three episodes were a biography of James J. Hill. That summer, a train named the Empire Builder inaugurated its cross-continental service. Ninety years later, it’s still running.

Courtesy: Great Northern Railway Historical Society