To understand the Deep Sea Fishermen’s Union (DSFU), the nation’s oldest surviving fishermen’s union, one needs to look back to its birth.

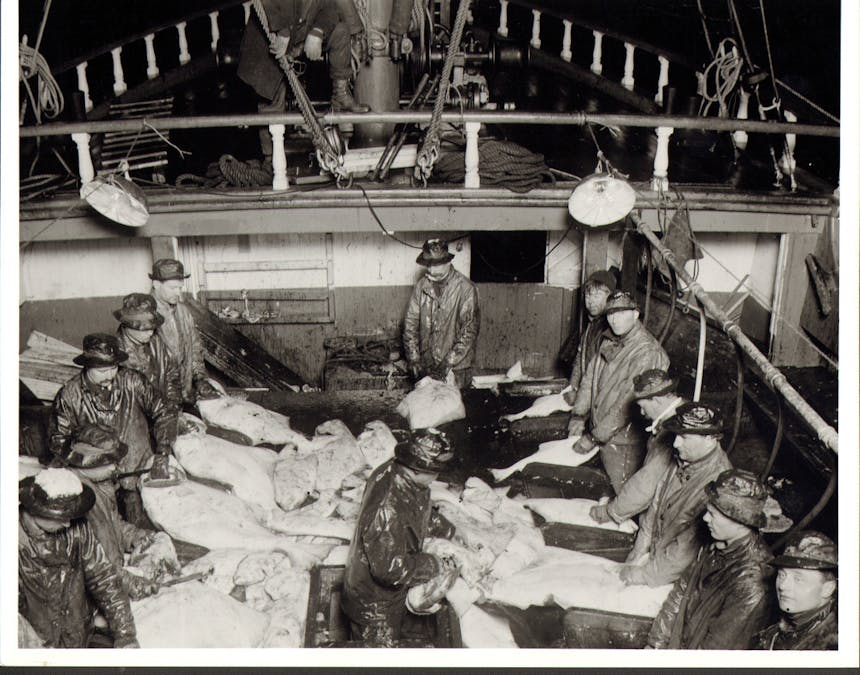

Back at the turn of the last century, a hardy group of men roamed the wooden docks of Seattle. Grizzled and gruff, they would spend days out on the unpredictable and often dangerous waters of the Salish Sea and nearby Pacific Ocean. Working long hours aboard wooden schooners, they would paddle out on small, wooden dory boats to manually haul baited lines bristling with thrashing halibut and sablefish up from the sea floor to bring back to the waiting schooner. It was a dangerous job, and fishermen routinely died, or just disappeared when out.

On November 4, 1912, a small group of fishermen met in a small hall downtown and formed the Halibut Fishermen’s Union of the Pacific, the precursor to the Deep Sea Fishermen’s Union. Over the next few years, they led numerous strikes against the Fishing Vessel Owners’ Association (FVOA) in an effort to gain better working conditions for their members and a more equitable share of the profits from the catch. Between the two an agreement was reached and a mostly congenial relationship was formed, one that still exists to this day.

Marsha Hoem working at the roller aboard the Coolidge.

The legacy of those old salts, many of them Norwegian immigrants, that gathered in that dark room in Seattle can be felt across the United States today.

Early in their existence, they recognized that certain fishing grounds were getting overfished, and that to sustain their industry they would need to implement changes previously unseen. Nursing grounds would be closed, the season would be shut down for certain winter months to give the fish time to recover, and certain self-policing measures were set in place. To ensure that the entire fishery was protected, they reached out to their Canadian brethren and helped facilitate the International Fisheries Commission. It was the first of many agreements between the countries that the union would help facilitate.

As women started to show up on the fishing boats, the union fought for them, too, and helped normalize working environments for them. On land, the wives of the seamen organized into the Halibut Fishermen’s Wives Association, a group that would quickly become one of the union’s loudest political voices. Meeting with presidents, senators, governors, and other leaders, they helped push Congress to establish the 12-mile limit in 1966. By pushing the fishing boundary further offshore, they helped protect US waters from overfishing by foreign vessels. Not content with this victory, they fought to push the boundary further out, and in 1976 helped the Magnuson–Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act get passed. This extended the boundary out to 200 miles, something that the Canadian government soon enacted too.

Nowadays, their battles have changed. Large factory trawlers can scour the ocean floors in hours, corporations have expanded, and so have their political voices, and the threats from foreign fleets depleting the oceans only grows. Each of the eight separate fishing areas surrounding America is having issues and the DSFU works with organizations to help. They focus on fishery science to ensure the overall health of the catch. When the fish go, so does their livelihood.

But at their core is their mission to advocate for the common deckhand, the oil that keeps the industry moving. Operating out of a small, non-descript building in the Ballard neighborhood in Seattle, they tirelessly advocate for the future of the industry and the continued financial success of all involved.

Photo provided by: Deep Sea Fishermen's Union